Opinion: The bizarre reality where Metro Vancouver's tallest towers are no longer in downtown

The image of towering glass condos rising from the seashore has become a defining feature of Vancouver. The city is often generously compared to the grand skylines of New York City and Hong Kong, particularly by locals, in a celebration of dense urban spaces with soaring towers at the ocean’s edge.

Currently, Vancouver’s tallest tower is the Living Shangri-La in the heart of downtown. Completed in 2009, Living Shangri-La rises 62 floors and stands at 196.9 metres tall, making it the defining peak of Vancouver’s skyline.

- See also:

- Opinion: Vancouver’s repressive tower height policies to limit shadows running amok

- Opinion: Arbitrary view cone height restrictions are strangling Vancouver’s potential

- Vancouver ranked 68th in the world for total number of skyscrapers

- New tower in Metrotown will become the tallest building in Metro Vancouver

- Metro Vancouver’s tallest building: New rendering of the proposed 82-storey tower

This tower, along with a few other recent additions, have helped reduce Vancouver’s tabletop appearance, but how tall is 196.9 metres?

Furthermore, how does Vancouver compare to other major cities in Canada and beyond? In short, the answers are discouraging: “Not very tall,” and “Unfavourably.”

Living Shangri-La is the tallest building in the downtown Vancouver skyline. (Shutterstock)

To start, one has to look no further than the suburbs of Vancouver itself to witness the shrinking height of the downtown skyline.

The general benchmark for a tower to be considered a “skyscraper” is a height of 150 metres or more. Today, there are 25 skyscrapers completed or currently under construction in Metro-Vancouver, yet only eight of them are located within the downtown peninsula.

The remaining 17 are found throughout the suburbs. Burnaby is home to 14 of these towers, while Surrey, Coquitlam, and New Westminster each claim a single tower for themselves.

This disparity between downtown Vancouver and the suburban cores will only continue to expand. If current documented proposals are included, Vancouver’s total increases to 16 towers, although two of these are located outside of the downtown peninsula, while the suburban total balloons to 32 skyscrapers or more.

New Westminster remains at a single tower, both Coquitlam and Surrey leap to five towers each, and Burnaby grows to a whopping 21 or more skyscrapers.

The growing Metrotown Skyline in Burnaby. (Ian Ius/Daily Hive)

Currently, Living Shangri-La still claims the top spot for Metro Vancouver, but this won’t last long.

Metro Vancouver’s new tallest is currently under construction in Burnaby’s Brentwood Town Centre, adjacent to SkyTrain’s Gilmore Station. Two Gilmore Place at 64 floors will stand at 214.8 metres tall when completed.

This victory though is likely to be short lived with the recent unveiling of the Concord Metrotown development, also in Burnaby. The tallest skyscraper in this project, situated on the southwest corner of Kingsway and Nelson Avenue, will rise 65 floors and reach a respectable height of 230.1 metres.

Once more, even this victory in Metrotown may be fleeting.

In Burnaby’s Lougheed Town Centre, a preliminary proposal for an 82-storey tower near that precinct’s SkyTrain station, with an estimated height of a soaring 265 metres, has been set into motion.

Artistic rendering of Concord Metrotown. Tallest tower is 230.1 metres (Concord Pacific)

While towers over 200 meters in height may seem extraordinary for those in Vancouver, they are commonplace elsewhere in Canada.

Living Shangri-La may still be holding on to the top spot in Metro Vancouver for another year or so, but in Canada, it already finds itself as only the 55th tallest tower in the nation. Its position plummets even further to 109th if all currently known proposals are included.

Montreal, Calgary, and Edmonton all possess skyscrapers that reach above Living Shangri-La,” but if transplanted into Toronto, it would find itself as merely the 35th tallest tower in the city — potentially falling to 75th place in the coming years.

In fact, Toronto is now piercing through the super-tall benchmark of 300 metres with the currently under construction SkyTower, which will stand an impressive 312.5 metres in height.

SkyTower in Toronto. (Pinna)

Even within Metro Vancouver, if all known proposals are constructed, Living Shangri-La will become only the sixth-tallest tower in the region. A rather dubious honour for the flagship tower of the region’s urban core.

Unfortunately, downtown Vancouver’s potential has been artificially stunted by a maze of overly restrictive height restrictions as a result of mountain view cone and shadowing regulations. While it may be foolish to completely remove such policies, their current form in and around downtown Vancouver can only be described as overzealous and counterproductive.

Their negative consequences reach far beyond that of simply limiting the aesthetic appeal of the downtown skyline.

This can best be observed around the SkyTrain hubs of Waterfront, Granville, and the soon to be Canada Line and Millennium Line interchange at Broadway-City Hall Station. In these highly transit-accessible zones, both office and residential densities are continuously stunned by the city’s strict height limiting practices.

Countless tower projects in these prime areas have been greatly reduced in scale for the sake of preserving arbitrary view corridors selected decades ago, often obscured by cloud cover, growing trees, or even a clutter of boat masts.

Even if a project is fortunate enough to escape the view cones and find itself on a parcel of land designated for higher buildings, it can still be cut short for nothing more than shadowing a select area for as little as 12 minutes a day during mid-winter.

Cluttered view cone “preserving” the view of The Lions. (Patkau Architects/Intracorp)

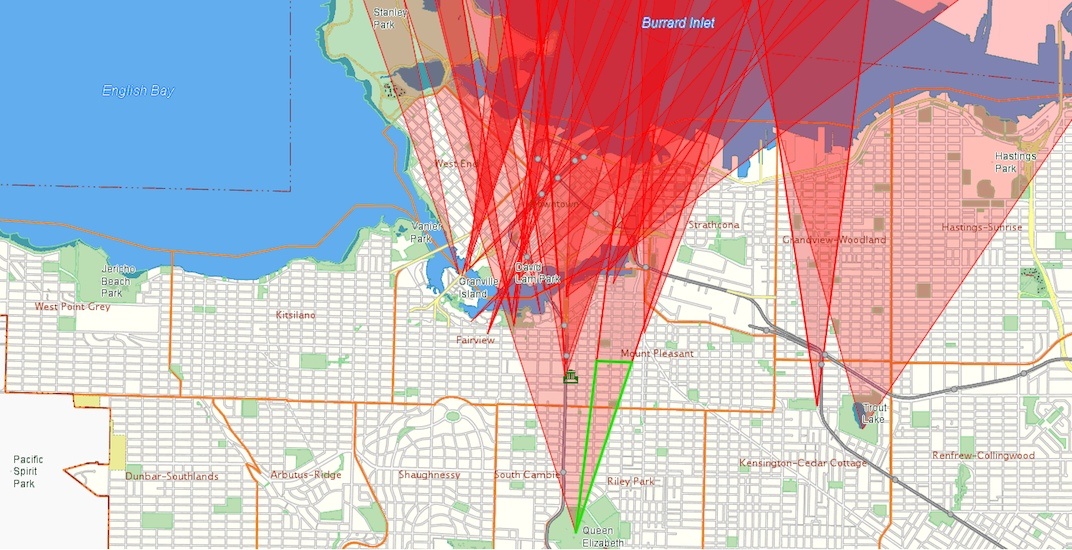

Map showing Vancouver’s view cone height restrictions. (City of Vancouver)

In the area around Broadway-City Hall Station, which will become one of the busiest transit exchanges in the region in 2025, these policies are so limiting that current projects being built directly above this future transit hub cannot even be described as towers.

The new office and retail development at 510 West Broadway on the southwest corner of Cambie Street and West Broadway is a laughable seven stories tall.

These policies not only add pressure to the current housing and affordability crisis, but they are also in direct contrast to the city’s self-described “green” principles, pushing development away from the city centre and away from mass transit.

Ironically, in an attempt to preserve the views of the green mountainsides of the North Shore, these strict height limiting policies have only encouraged housing sprawl to climb higher up those very same mountains.

Artistic rendering of the redevelopment at 510 West Broadway directly above the future hub station of Broadway and Cambie – the southwest corner of the intersection of Cambie Street and West Broadway. (W.T. Leung Architects/Pacific Crown Management Company Ltd.)

To the south of Vancouver, the city of Seattle also finds itself surrounded by the sea and mountains but appears to have found a better balance between celebrating both the splendour of the natural surroundings and the embrace of the big city form.

Currently, there are six towers taller than Living Shangri-La in downtown Seattle, the tallest being the stately 76-storey Columbia Centre at 284.2 metres tall.

This may soon be surpassed by the currently proposed 4/C tower that is the city’s first potential super-tall at the height of 313.6 metres.

Potential future Seattle skyline with proposed 4/C tower. ( LMN Architects)

Despite the opposition, some have towards taller towers in downtown Vancouver and the tangled mess of policies a project must navigate, once constructed it is hard to imagine the city without them.

Both Living Shangri-La and Vancouver’s Turn (Trump Tower) have greatly improved the view of downtown as seen from the North Shore. Vancouver House has similarly vastly improved the downtown skyline as seen from various locations throughout the city.

There is much more to the Vancouver skyline than simply viewing it from the south of Vancouver City Hall. A taller, more dynamic skyline would greatly improve the downtown skyline as seen from more directions than it would hinder.

The Vancouver skyline seen from the North Shore. (Ian Ius/Daily Hive)

This week, a new proposal at 1045 Haro Street is challenging a few of these height limiting policies.

One of the major roadblocks for this project is an increase in shadowing on the north side of Robson Street by no more than 2%, all of which would occur during the winter months. The tower itself is only 177 metres tall, which would potentially place it as low as the 176th tallest tower in Canada when completed.

One can only imagine what could be done if all this effort the City of Vancouver expels on regulating and enforcing these archaic regulations was instead directed towards revitalizing the city’s laneways or keeping the city’s local parks safe and clean for all to enjoy.

It is time for Vancouver’s to relax its height limits smothering the downtown peninsula and beyond, especially around key mass transit hubs, and fully embrace the potential of its urban beauty.

Artistic rendering of 1045 Haro Street, Vancouver. (Patkau Architects/Intracorp)

Downtown Vancouver’s skyline growth. (WKK Architects/IBI Group/Henson Developments)

- See also:

- Opinion: Vancouver’s repressive tower height policies to limit shadows running amok

- Opinion: Arbitrary view cone height restrictions are strangling Vancouver’s potential

- Vancouver ranked 68th in the world for total number of skyscrapers

- New tower in Metrotown will become the tallest building in Metro Vancouver

- Metro Vancouver’s tallest building: New rendering of the proposed 82-storey tower