Opinion: Vancouver’s repressive tower height policies to limit shadows running amok

Finding a suitable site in Vancouver where tall buildings can be built is increasingly akin to playing the child’s game of “the floor is lava.” They are becoming absurdly rare with layers upon layers of considerations, priorities, strategies, and policies to consider.

For decades, property owners and developers have had to contend with mountain view cone height restrictions, but more recently they now also need to overcome the added obstacle of shadowing — the shadows that proposed new building cast on their vicinity, with particular focus on public parks, plazas, and other public spaces.

- See also:

The idea is to provide such spaces with an optimal level of solar access, the ability of a space or building to receive sunlight without obstruction from neighbouring buildings.

This is an important consideration for the city, even if a shadow touches a small part of a public space deemed to be important for a very short period of the day, during a certain time of year when the sun is low.

“We certainly recognize that solar access is a critical element of a public space, especially in a northern city such as Vancouver with cooler temperatures,” said Neil Hrushowy, the director of community planning at Planning, Design, and Sustainability for the City of Vancouver, during a recent city council meeting on public spaces.

“The basic human needs, you have to feel comfortable if you’re going to spend time. It’s easy to get people to walk down streets when you use high density and good transit, and people have to get around. It’s another thing to create public spaces where people want to stop and spend some time, meet up with some friends, and have that very important social aspect of their lives.”

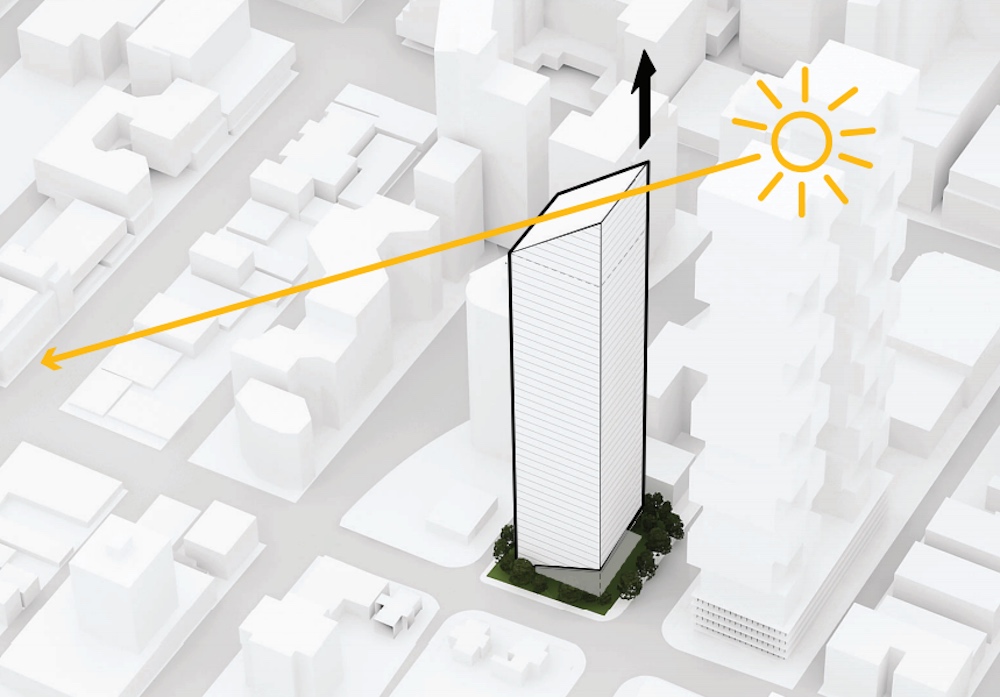

Triangular-shaped peak for the design of 1063-1075 Barclay Street to provide solar access on Robson Street. (ACDF Architecture/IBI Group/Pacific Northern Developments)

The municipal government has been very clear with its intent of improving existing public spaces and creating new additional spaces in downtown to address the needs of the growing population and workforce.

But with new parks and plazas planned or already under construction, there are not many sites left that can be redeveloped into tall buildings due to considerations to shadowing impacts and view cones. And a growing number of sites suitable for additional density through height, particularly those within the Central Business District and near SkyTrain stations, have been wasted by shorter towers due to the regulations.

More troubling is the city’s recent expansion of where shadowing should be avoided — intersections and shopping streets.

This is a major cause for concern for Charles Gauthier, the president and CEO of the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association (DVBIA). He says he does not dispute the need to consider solar access for public parks, but he is disputing city staff’s emerging priority for shopping streets.

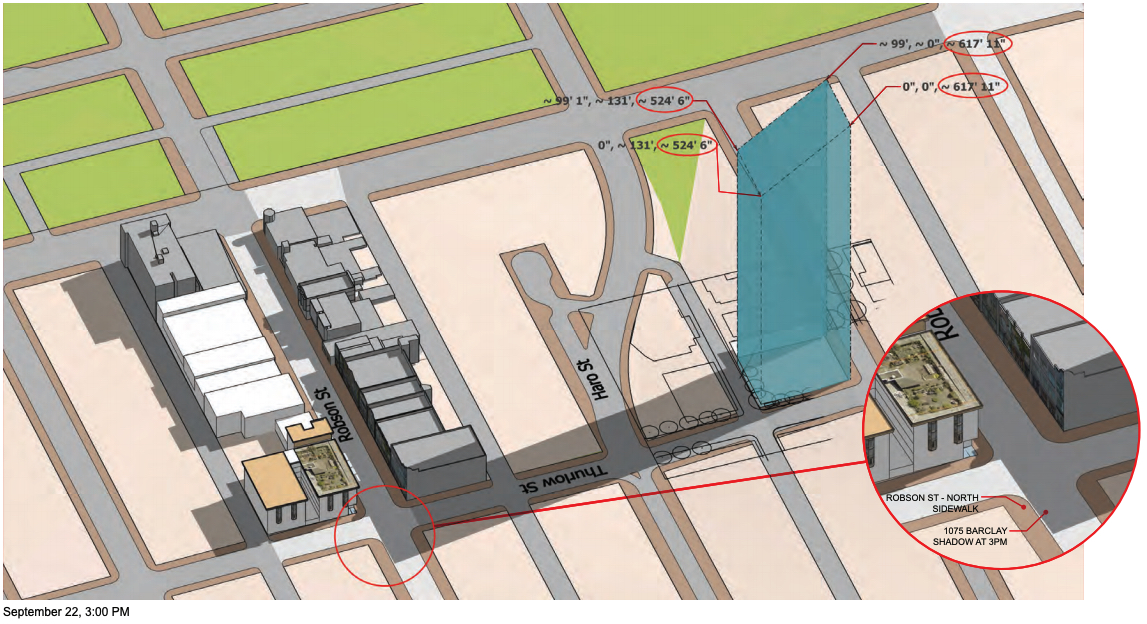

He pointed to Robson Street being a target area for the protection of solar access earlier this year, specifically from the shadows cast from several new tower projects towards the south along the Thurlow Street corridor.

Gauthier says city staff made unilateral decisions on changing when the sun needs to hit the sidewalk on the north side of Robson Street, especially between Thurlow Street and Burrard Street. City staff have since backed off on this idea to some extent in favour of some further analysis and consultation with developers.

Shadowing on Robson Street from 1063-1075 Barclay Street on September 22 at 3 pm. (ACDF Architecture/IBI Group/Pacific Northern Developments)

Pacific Northern Developments’ proposal for 1063-1075 Barclay Street — the northeast corner of the intersection of Thurlow Street and Barclay Street — calls for 469-ft-tall, 48-storey tower with 295 units of strata housing and 79 units of social housing.

Not only is this tower considerably shorter than the 550-ft-tall limit set for the site by the city’s West End Community Plan, the top five floors are cut to create a triangular-shaped peak that protects solar access on the north side of Robson Street, located two blocks away.

Artistic rendering of 1063-1075 Barclay Street, Vancouver. (ACDF Architecture/IBI Group)

Similar solar access considerations are provided to the projects to the south, specifically Bosa Properties’ 1040-1080 Barclay Street (twin towers up to 458 ft with 481 strata housing units and 162 social housing units), and Henson Developments’ 1059-1075 Nelson Street (586-ft with 102 units of social housing, 51 market rental homes, and 328 strata homes).

1059-1075 Nelson Street’s rezoning application was recently approved by city council, but shadowing on the adjacent Nelson Park and Robson Street was a major source of consternation, despite the all the benefits from $70-million worth of affordable homes, including units suitable for larger families.

Artistic rendering of Bosa Properties’ twin tower proposal at 1070 Barclay Street in downtown Vancouver. (Buro Ole Scheeren Architects/Bosa Properties)

Shadowing of Bosa Properties’ 1040-1080 Barclay Street (red) and Westbank’s The Butterfly at 1019 Nelson Street (blue) on March 21 at 4 pm. (Bosa Properties)

Shadowing of Henson Developments’ 1059-1075 Nelson Street (red) and Westbank’s The Butterfly 1019 Nelson Street (blue) on March 21. (Henson Developments)

In another emerging contentious area for solar access considerations, Gauthier is a staunch supporter of the recently rebuilt North Plaza of the Vancouver Art Gallery, and believes it is an important spot to try to retain some sunshine during certain times of the day. But like shopping streets, he wants the city to temper any idea of protecting solar access deep into the evening when there are longer shadows, given the inevitable negative impact it would have on some proposed developments.

“We don’t have a solar access issue in the city, we have a housing affordability issue. What I would be concerned about is if we layer solar access and made it extremely restrictive in combination with the view corridors. That could be extremely prohibitive in terms of what can be built in downtown,” Gauthier told Daily Hive Urbanized.

“I think it could have a damaging effect on the viability of housing projects and potentially on job space projects. That is the concern. We really feel we need to be consulted and understand what they’re trying to achieve in doing this, and better understand what the impact will be if they do this.”

Jon Stovell agrees. He is the president and CEO of Reliance Properties, which has been forced to substantially curb the height and designs of their most recent tower proposals in downtown due to city staff’s insistence on increasing the extent of shadowing on public spaces.

In January 2019, city council approved his firm’s rezoning application for 1166 West Pender Street — a 399-ft-tall, 32-storey office tower. But due to the tower’s shadowing on the southernmost edge of Harbour Green Park, they had to eliminate six floors in an earlier design, and cut a wedge shape on the top 10 floors in the final design to increase the solar access to the park.

Shadowing of 1166 West Pender Street on the perimeter of Harbour Green Park. (Reliance Properties)

The resulting triangular peak reduced about 11,000 sq. ft. of office space, and made the top floor layouts inefficient — all for the sake of the 2% increase in geometric shadow area on the park for about 30 minutes a day during a limited period in the year.

If it were not for the shadowing regulations, Stovell says Reliance Properties would have pushed ahead with a 550-ft-tall tower. This would have provided the tower with an additional 150,000 sq. ft. of office floor area, enough space to employ about 1,000 people.

November 2018 rezoning artistic rendering of 1166 West Pender Street, Vancouver. (Neil M Denari Architects/Hariri Pontarini Architects/IBI Group Architects/Reliance Properties)

Just south of his tower site, across the laneway, is the under-construction 1133 Melville Street office tower by Oxford Properties. This will be downtown Vancouver’s tallest office tower, with a height of 530 ft and 36 storeys, but two top floors — about 12,000 sq. ft. of floor area — had to be chopped off to address city staff’s same concerns on the shadowing of Harbour Green Park.

Stovell notes his firm had eyed on redeveloping another property in the immediate vicinity, but they decided not to move ahead with an application until the same shadow impacts are reconciled.

This is an issue even though these sites fall within the city’s General Policy for Higher Buildings, which permits heights of 550 ft within much of the Central Business District. But view cones and shadowing override this policy.

“These are coral reef policies that build up over time, and it rips the bottom of every ship that tries to cross it,” Stovell told Daily Hive Urbanized.

“Many projects can’t make it over the reef because there’s just too many conflicting policies, and builders can’t figure out how to meet every one of them. It kind of falls on the applicant to solve all the policy conflicts.”

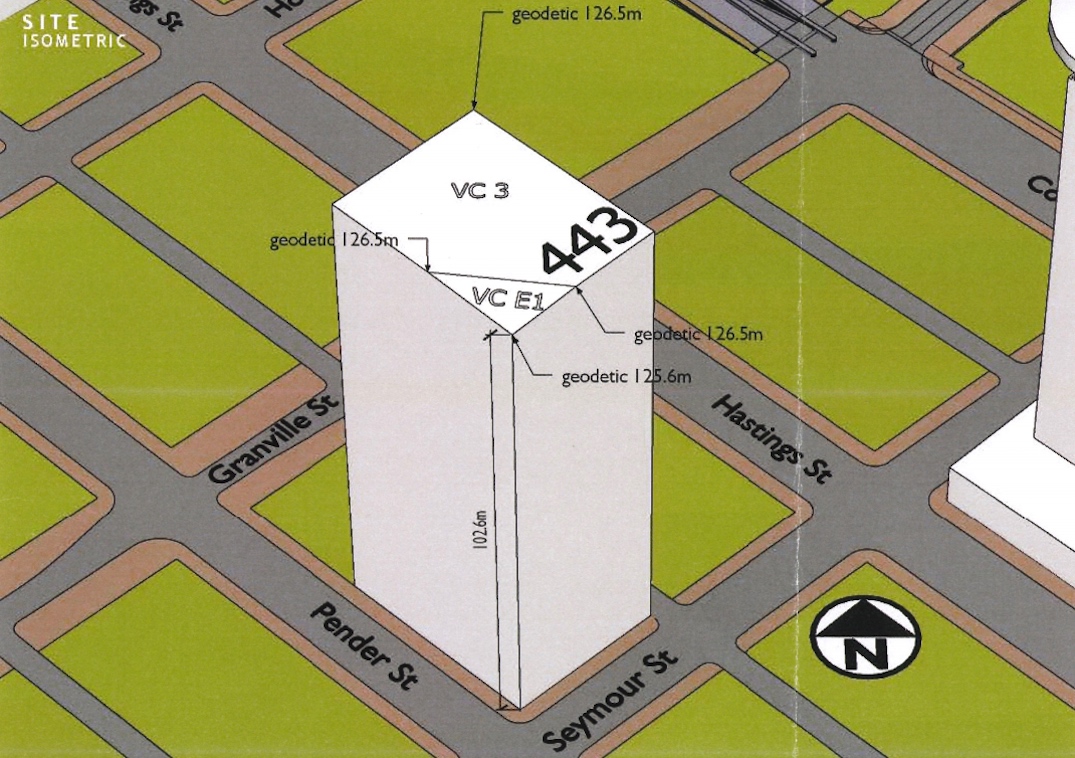

Further east, city council recently approved Reliance Properties’ proposal for a 338-ft-tall, 29-storey office tower at 601 West Pender Street — the northwest corner of the intersection of Seymour Street and West Pender Street.

If it were permissible, they would have proposed an office tower up to 40 storeys — about 170,000 sq. ft. of additional office floor area for over 1,000 employees. However, the actual buildable height is curbed by view cones.

Artistic rendering of 601 West Pender Street, Vancouver. (Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates/Chris Dikeakos Architects/Reliance Properties)

View cones affecting 601 West Pender Street. (Reliance Properties)

In the mid-2000s when West Pender Place at 1499 West Pender Street in Coal Harbour was being designed, Stovell says his team was required to swap the location of the short building and the tall tower to minimize the shadowing on Coal Harbour Park. He agreed with this decision to rearrange the layout of the complex as it was “all about good design,” but they still lost about five storeys on the short building after shifting the building.

He says this was the cost for a “minimal and short-lived shadow,” and ever since the firm has never done a tall building where shadow has not resulted in some change to the design or in some cases the unviability of the project.

West Pender Place at 1499 West Pender Street. (Reliance Properties)

“What has been happening with shadows is they kind of have gone from something that needs to be considered and thought about as part of design to this outright prohibition on any shadowing, which in many cases is not supported by current city council policies,” said Stovell.

“It’s a bit of a runway, non-policy, discretionary approach in the planning department. The development community has been complaining about it to staff. The result is a lot of times a lot of projects don’t see the light of day, and with all the benefits those projects might bring like community amenity contributions (CACs) creating daycare, social housing, development fees, and other amenities. A lot of them don’t see the light of day because they’re stopped in their tracks because of some shadowing. Same thing goes with view cones.”

According to Stovell, the development community is now used to working around view cones, but the new rigour and inflexibility from city staff on shadowing has become incredibly problematic.

They used to consider shadows for the spring and summer solstices between 11 am and 2 pm. Now they are being requested to perform shadow studies for 4 pm and 5 pm, when the shadows are far longer. On another recent project, he says, they were asked to model shadows until 7 pm.

Elsewhere in the city, Reliance Properties also had to cut the height of its Burrard Place tower — currently under construction at 1290 Burard Street — because of the shadowing on the intersection of Burrard Street and Davie Street for one hour a day.

Artistic rendering of 902 Davie Street, Vancouver. (Neil M Denari Architects/Bingham Hill Architects)

On the northern end of the same city block at the site of the 7-Eleven convenience store, 902 Davie Street, the developer is proposing to build 158 secured market rental homes and over 30,000 sq. ft. of retail and office space within a 300-ft-tall, 25-storey tower.

The height and the highly unusual and inefficient shape, almost a 45-degree chamfering within the upper floors, is the product of both considerations for a view cone and the minimal shadowing on the intersection of Burrard Street and Davie Street.

“With these small floor plates, it makes you just want to cut the whole top of the building off,” said Stovell.

Artistic rendering of the MEC store redevelopment at 130 West Broadway, Vancouver. (Neil M Denari Architects/IBI Group Architects)

Over on the Central Broadway corridor, Reliance Properties owns the former MEC Vancouver flagship store at 130 West Broadway — a short five-minute walk from SkyTrain’s Broadway-City Hall Station. The proposal is for a mixed-use redevelopment with 23-storey twin residential towers on top of a large lower podium with restaurant and retail space, including a grocery store. The total floor area is 275,000 sq. ft.

He says this particular project has been in limbo for the past four years because view cones and shadowing combined are major constraints.

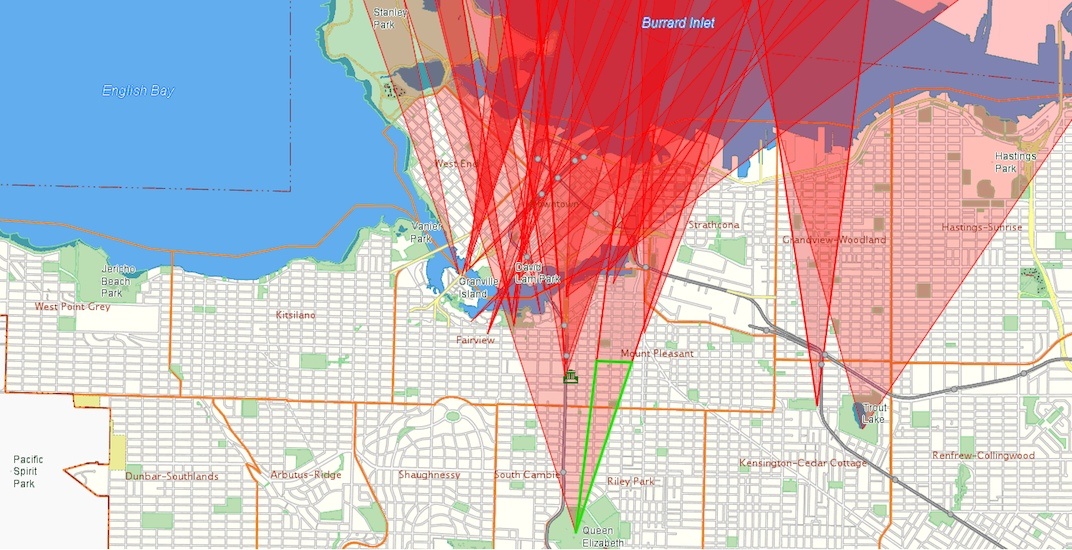

“The view cones from Queen Elizabeth Park create a huge suppression on the northern areas of the city, the entire downtown Vancouver peninsula and pretty much all of Central Broadway,” he added.

“We’re already building on the site and going through all the necessities and disruptions for the neighbourhood. Do you really need to cut it back and make it less efficient because of shadow and view cones?”

For these reasons, and depending on the outcome of the Broadway Plan, they have yet to submit a rezoning application.

Map showing all of Vancouver’s view cone height restrictions. (City of Vancouver)

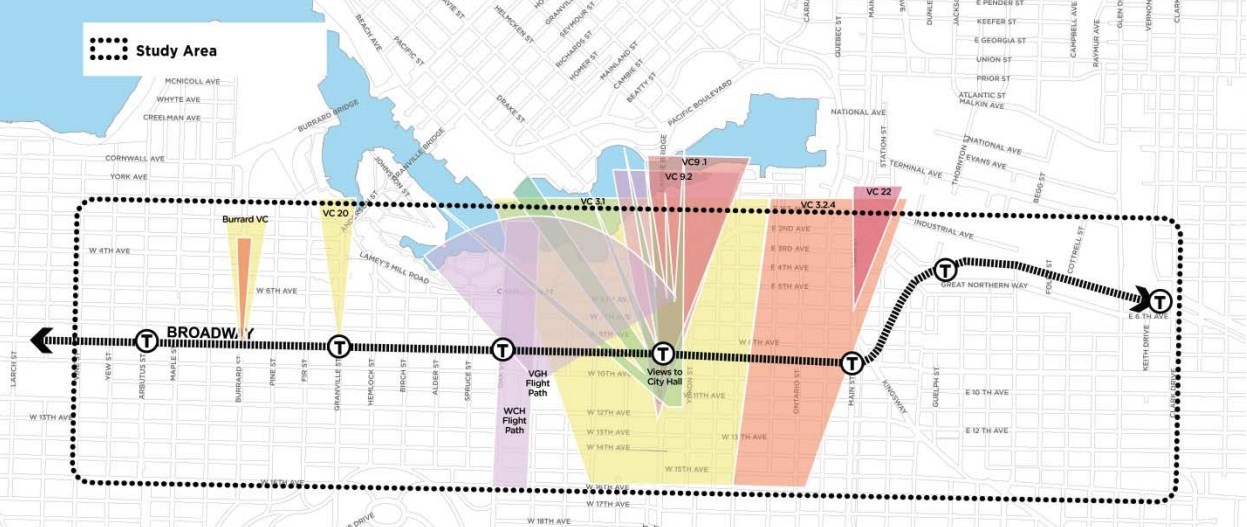

View cones and flight path height restrictions over the Broadway Corridor. (City of Vancouver)

There is also trepidation with the rezoning application for 2538 Birch Street — the former Denny’s restaurant site at the intersection of West Broadway and Birch Street, near the future South Granville Station of SkyTrain’s Broadway Extension.

Jameson Development Group wants to build a 278-ft-tall, 28-storey tower with 258 secured rental homes, including 200 market units and 58 below-market, moderate-income units, plus approximately 30,000 sq. ft. of retail and office on the lower three levels.

Despite the economic and social benefits this project would generate, much of the public discourse that is opposed to the project centres on height and shadowing. It would be the second tallest building in the corridor, just after Vancouver General Hospital’s Jim Pattison Pavilion.

“I’m not saying that shadowing shouldn’t be considered and thought about in design and minimized, but it needs to be done in balance with other aspirations that we have for the community, including the creation of job and residential space,” said Stovell, adding that there are numerous examples by every large developer where they have to reduce the height for shadow and views for their projects within the downtown peninsula and Central Broadway.

“Even social housing projects are being impacted,” he continued.

May 2019 artistic rendering for 2538 Birch Street (formerly 1296 West Broadway) in Vancouver. (IBI Group/Jameson Development Group)

Other developers, understandably, were unable to comment on these issues because they have applications currently under review.

But a commercial real estate consultant, who wished anonymity over the sensitive nature of the matter, said view cones and increasing shadowing considerations have had an “astronomical negative economic impact on Vancouver.”

Over the past 20 years, they estimate restrictive policies — especially on building form and heights — have cumulatively robbed the city of as much as nine million sq. ft. of residential and office floor area, based on their accounts of projects that have been privately internally envisioned and put on hold or cancelled by developers, as well as projects downsized or rejected by city staff in the pre-application process.

Many larger project scopes often do not see the light of day — the public never knows about them — when the restrictions make the developments financially unfeasible, and they are stopped in their tracks before reaching pre-application public consultation.

They emphasize the market demand for far larger and more efficient developments exist, but it is being artificially suppressed: It is no coincidence that virtually every proposed project has reached their allowable height ceiling as permitted by the view cones.

January 2019 artistic rendering of The Post redevelopment in downtown Vancouver. (QuadReal Property Group)

If QuadReal Property Group was provided with leniency for The Post, the redevelopment of the old Canada Post building in downtown, they would have built more office space for Amazon and other potential tenants — far more than the 1.13 million sq. ft. Blame the view cone crossing through the city block that limits heights to just 350 ft, they say.

In many cases, they say, developers have turned their attention to suburban cities, with the main benefactors being Burnaby and Coquitlam — avoiding the red tape and inconsistencies of the regulations and planning staff of the City of Vancouver.

The consultant notes its estimate on Vancouver’s lost potential from restrictions does not include a tech hub development up to $5 billion spearheaded by a Toronto-based investor, which could have created job space for tens of thousands of people in Vancouver. But it was declined by the municipal government over political reasons unrelated to view cones and shadowing.

After the political leadership at the time signalled this project would not be considered, even though it had federal support, Hootsuite’s Ryan Holmes and Westbank’s Ian Gillespie went on to create their smaller Main Alley tech hub, which is currently under construction just west of the intersection of Main Street and East 4th Avenue. There will eventually be a tech campus of five buildings with nearly 600,000 sq. ft. of total office space.

But this is all part of the consistent theme in Vancouver where economic prosperity goals do not even come as second fiddle.

Contrast this to the mantra of the municipal governments of Toronto and Calgary, which are far more aggressive with economic growth given the obvious societal benefits. It is also increasingly apparent that this is clearly understood by a number of other Metro Vancouver municipalities, who see the region’s namesake city resting on its laurels and no longer offering regional economic and political leadership. For some of these suburban cities, Vancouver is now a jurisdiction to be in competition with, perhaps even toppled.

Artistic rendering of Henson Developments’ 1059-1075 Nelson Street (left) Bosa Properties’ 1070 Barclay Street (centre), and Westbank’s The Butterfly at 1019 Nelson Street (right). (WKK Architects/IBI Group/Henson Developments)

What this city fails to understand is livability in the Vancouver context is about the tangible aspects, specifically affordable housing that is achievable for developers to build and residents to live in, self-reliance through catalyzing good employment opportunities and upward mobility, and convenient access to the region’s largest concentration of opportunities.

Unfortunately, contemporary urban planning often does not take into account these issues, it only cares about subjective “good design.” But just imagine all that could be achieved by Vancouver if economic prosperity had the same footing as its “greenest city” aspirations.

All of this starts with lifting some of the most restrictive regulations on building form and height, and other pedantic policies to protect things that are ultimately highly intangible but have been provided with a disproportionate amount of weight over how decisions are made.

“We’ve been talking to the city many years now to try to get rid of these overlapping regulations or at least prioritize when there’s conflicting objectives. For example, we want daycare but we don’t want a shadow, so which one is more important?” added Stovell.

“If they’re both equally important in the views of the bureaucrats, then the politicians need to make that decision. Those tradeoffs very often don’t make it to the floor of city council.”

Artistic rendering of 1059-1075 Nelson Street, Vancouver. (WKK Architects/IBI Group/Henson Developments)

In their review of rezoning applications, city councillors in public meetings have often commented on how a developer should be bringing more to the table when it comes to affordable rental homes, lower rental rates, daycare, and/or a higher cash contribution on levies and CACs. But the rule to thumb to remember is the level of public amenities provided is proportional to the permitted density, often through added height due to lot size constraints.

“There needs to be a clearly articulated policy that measures and informs the political leadership about the pros and cons of shadowing and what that costs in terms of other things that might be delivered through development. City council does not have the benefit of knowing what is being given up,” continued Stovell.

“At least the view cone policy is a published public policy that has been approved and reviewed by city council. I disagree with it, but I accept their will on that regard. But the shadow is so discretionary, you never know how it’s going to go.”

Gauthier said that in meetings with the city last fall and earlier in 2020, “solar access was put at the top of the list instead of trying to support the growth of the economy.”

“Economic growth should be more of a priority now more than ever. You do that by approving projects that are coming forward.”