Vancouver's top five most salacious and surprising scandals from the past

This month, local walking tour company Forbidden Vancouver has launched a brand-new tour, The Monumental Scandals Tour. The experience is a two-hour stroll through downtown that visits the city’s most famous heritage buildings, including the Marine Building, Hotel Vancouver, and the Vancouver Art Gallery. On the way, guests will hear tales of scandal and intrigue from our city’s past.

To celebrate the launch of this new Vancouver experience, below are five scandals from Vancouver’s history.

Marie Lloyd

England’s Marie Lloyd was a music hall star of London’s stages, who performed in Vancouver in 1914 on her North American tour. She was renowned for her risqué act, which included singing and dancing… often with a heavy dose of innuendo. One of Lloyd’s most scandalous songs was “I sits among the cabbages and peas,” best imagined in a thick Cockney accent.

English music hall star Marie Lloyd performed in Vancouver in 1914. Louis Saul Langfier (1859–1916) – National Portrait Gallery

Lloyd’s most famous number was her “ankle watch dance.” At the end of the song, she would raise the hem of her skirt a few inches, showing her bare ankle, upon which was fastened a watch.

Lloyd’s opening night act at Vancouver’s old Orpheum theatre caused a huge uproar. Newspaper editors were shocked that women present in the audience had been subjected to such filth. An editorial in the World News called her act “lewd” and said it caused “complete disgust.” The mayor at the time, Truman Baxter, threatened to take the Orpheum’s licence away if Lloyd repeated her salacious act the next night.

Ultimately, Lloyd did tone down her routine a little for subsequent dates, but as her final night in Vancouver drew near, rumours began that she was planning to take things really over the top. So, moments before going on stage, the mayor pulled the plug on her final show, leaving her backstage in a fury. Witnesses at the time said it took several men to restrain Lloyd, one of whom she sank her teeth into.

Corrupt Prohibition Commissioner Walter C. Findlay

Vancouver’s flirtation with prohibition only lasted from 1917 to 1921, but the temptation to make fast money from illegal booze was too much for some to resist. While mobsters and bootleggers filled their pockets selling liquor to a thirsty public, it was left to the BC Prohibition Commissioner to keep things under control.

The province hired Walter C. Findlay as its prohibition commissioner, a man who’d campaigned for prohibition himself as the secretary of the People’s Prohibition Movement. He was well known for his sturdy moral backbone.

Front page of the Vancouver Sun, Dec. 12, 1918.

Findlay’s backbone proved more flexible than people had realized. In 1918, he was busted trying to smuggle a vast quantity of high-end whisky into Vancouver on a train from Quebec. His plan was to store the booze in a private warehouse in Gastown and then sell it on the black market. When he was fined $1,000 in court for his crime – which would be about $20,000 in today’s money – he took out his wallet and paid the fine on the spot, in cash.

The Lennie Commission and the VPD “Bribe Book”

Rumours swirled around Vancouver in the 1920s that top cops, and perhaps even the mayor himself, were on the take from crime bosses in the city. The Lennie Commission of 1928 was created to get to the bottom of it all. Remarkably, many crime bosses were only too willing to take the stand and testify. Gambling kingpin Shue Moy was incensed that the police still raided his gambling joints, even though he’d paid handsome bribes to detectives.

Vancouver Mayor LD Taylor in 1929. Vancouver Archives.

Shue Moy went on to state he was a friend of Vancouver Mayor LD Taylor and admitted he had often visited the mayor’s private home. He had also contributed financially to the mayor’s election campaigns and invested in a business the mayor owned. Bear in mind, Shue Moy was well known in Vancouver as “The King of the Gamblers.”

Under pressure, the VPD owned up in court to keeping a “bribe book,” in which they documented the many bribes they received. They used the money to entertain officers visiting from out of town, throw banquets, and buy gifts.

Taylor remained in office but was ultimately thrown out by voters. How many police officers were fired once the commission was over? Zero.

Construction of the Lions Gate Bridge

It’s difficult today to imagine Vancouver without the iconic Lions Gate Bridge. Picture Stanley Park as one uninterrupted forest and think of yourself wandering the seawall without bridge traffic thundering overhead.

In fact, in the 1920s, the citizens of Vancouver were dead set against the construction of the bridge precisely because they didn’t want a road built through Stanley Park. At a public vote in 1927 the people of Vancouver rejected the idea.

The Lions Gate Bridge seen from the Stanley Park seawall in 1948. Photographer: Walter Edwin Frost, Archives Item #CVA 447-129.

As the Great Depression bit harder and harder, creating jobs became the priority. In a second public vote in 1933, the tide of public opinion changed, and Vancouverites approved the bridge. Its construction was funded by the Guinness family, of beer-making fame. Having purchased 4,700 of prime real estate on the forested slopes of West Vancouver, the Guinness family knew they needed a bridge if they were going to realize the maximum potential of their investment. Their development was called the British Properties and remains one of the city’s most exclusive neighbourhoods to this day.

But is this really a scandal, or just a savvy business deal? Well, peer a little closer and the story of the Lions Gate Bridge and the British Properties isn’t pleasant. In 1933, the City of Vancouver passed a by-law that “no Asiastic person shall be employed in or upon any part of the undertaking or other works” related to the construction of the bridge. The City wanted jobs, but only for white people.

The northern end of the bridge lands directly on Squamish reserve land, yet the Squamish Nation were not consulted about the bridge’s construction and received scant compensation. Their land was forcibly surrendered under the terms of the Indian Act.

Squamish Chief Simon Baker later said “We had no say. We were compelled to surrender the land. The government took over. I couldn’t believe what they did. It was done under cover.”

The government assessed the land value at $3,270, which even in 1930s money massively undervalued the 9+ acres of land that of course still houses the bridge to this day. Along similar lines, neither the Squamish nor Tsleil-waututh Nations received any compensation for the sale of their unceded territory to the Guinness Family.

Once built, homes in the British Properties were restricted to white owners only, with Black, Asian, and Jewish ownership prohibited. Today, the British Properties is racially diverse and the covenants that once existed on property titles have been removed or are unenforceable.

Old Vancouver Stock Exchange

Prior to its merger with the Canadian Venture Exchange in 1999, the Vancouver Stock Exchange enjoyed a colourful past. Much attention in recent years has been given to the allegations of major money laundering schemes involving BC’s casinos, yet the old stock exchange was a haven for money launderers back in the 1980s.

In those days, investors could drop off large sums of cash in return for stock certificates, with some brokers disinclined to question the source of the funds. Allegedly, Filipino dictator Ferdinand Marcos embezzled millions of dollars through First Vancouver Securities, who later lost their licence as a result.

Money launderers weren’t the only people attracted to the lax regulations of the Vancouver exchange. A revolving door of scam artists endeavoured to defraud investors by releasing false information in an effort to drive up stock prices.

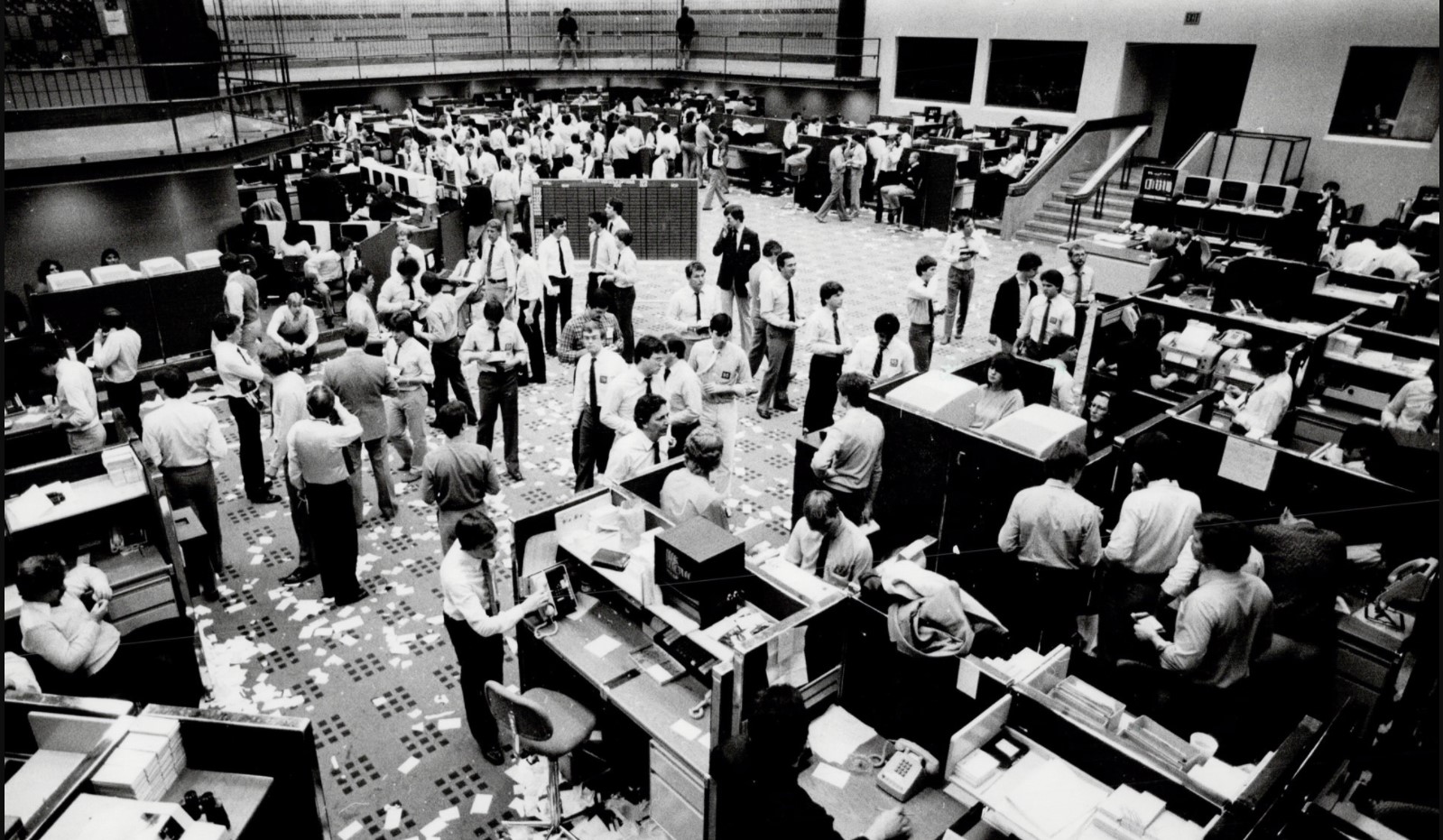

Vancouver Stock Exchange trading floor, 1983. Jeff Goode photo, Toronto Public Library 0105174f.

In 1981, Gold company New Cinch Uranium Ltd. put out false data saying it had found huge gold reserves on its property in New Mexico. Their stock price went up ten times in value before collapsing when it turned out their data was made up. In 1985, CHoPP Computer Corp. claimed it had created a super-computer one hundred times faster than the world’s fastest computer. When it was discovered that the computer did not exist, investors lost a fortune in the resultant stock price collapse.

Few criminal charges were ever brought against executives or officers of the fraudulent companies. Many of the con artists would just dissolve their company and move on to the next scam, apparently.

The Monumental Scandals Tour

Discover more scandalous Vancouver history on Forbidden Vancouver’s Monumental Scandals Tour. Every Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday, and Sunday at 10 am. Tickets are available here and cost $32 for an adult and $29 for a senior or young person.

Forbidden Vancouver guide Rob Teska leading the Monumental Scandals Tour. Credit: Forbidden Vancouver Walking Tours.