Opinion: Surrey Light Rail will be one of Metro Vancouver's worst transportation mistakes

Nearly a decade after the opening of the Canada Line, Metro Vancouver is once again on the verge of building another severely under-built rail rapid transit line.

This time, the controversy surrounds the Surrey Newton-Guilford light rail transit (SNG) project – one of the highest priorities of the City of Surrey under the leadership of Mayor Linda Hepner’s Surrey First civic party.

The SNG is a 10.5-km long, ground-level light rail transit (LRT) project that runs down busy arterial city streets between Newton and Guildford, with 11 stations including several stations serving the emerging downtown Surrey area in Whalley and connecting passengers to the existing SkyTrain Expo Line.

The L-shaped route will run west from 152nd Street in Guildford along 104 Avenue to City Parkway, south along City Parkway to 102 Avenue, west along 102 Avenue to King George Boulevard, and then south along King George Boulevard to the Newton terminus near 71 Avenue and 136b Street.

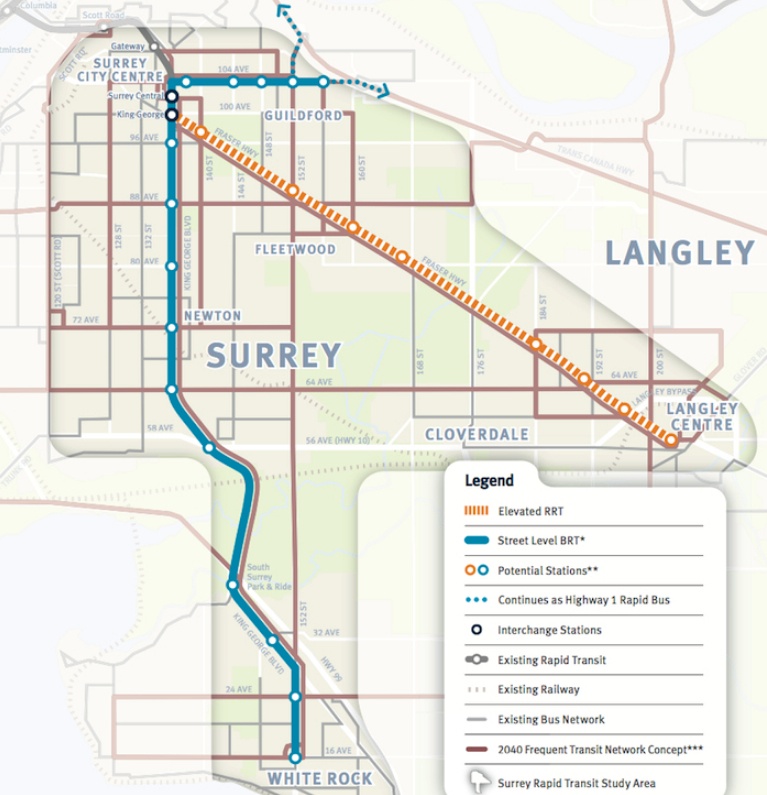

Map showing the route and station locations of Surrey Light Rail, with the Surrey Newton-Guildford Line highlighted and the Surrey-Langley Line slated as a future phase. Click on the map for an enlarged version. (TransLink)

Any transit expansion might seem appealing in Surrey, which often bellyaches over its limited and infrequent public transit services, but what is being proposed is not the transportation and mobility solution both Surrey and the rest of the region needs and deserves.

A source that was close to the project told Daily Hive under the condition of anonymity the SNG is now expected to cost $1 billion, and this figure could potentially rise even higher.

This budget does not include the proposed second line to Langley, giving the LRT endeavour a combined cost of at least $2.6 billion, according to the municipal government. Both projects were originally said to carry a cost of $2.18 billion.

Artistic rendering of Surrey Light Rail running down the middle of a street of a redeveloped area – sometime in the future. (TransLink)

With such costs, the LRT project that is being insisted by the City of Surrey is closing in on the same costs as a more superior fully grade-separated, elevated SkyTrain line, despite LRT being much slower and less reliable than SkyTrain and having an ultimate capacity that is just a small fraction of SkyTrain’s.

Moreover, the SNG as designed is being built for all the wrong reasons.

When the Canada Line was being deliberated in the early-2000s, the debate amongst our elected representatives and the media centred on doubts over the ‘high’ ridership projections and its perceived unaffordable construction cost, which led to discussions over ways to cut down on costs by cutting back on its design.

As the saying goes, history does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

Here is why Surrey’s LRT endeavour being forced on TransLink is shaping up to be one of Metro Vancouver’s worst and most expensive transportation investment mistakes:

Ultimate capacity is 27% of the Canada Line’s capacity

Despite its projected high cost, the SNG’s design capacity will be far from future-proof and places it on the low end of LRT capacities – closer to a streetcar.

Last week, SNG planners released the project’s Environmental and Socio-Economic Review Draft Terms of Reference, which revealed that the new LRT line will have an ultimate design capacity of just over a quarter of the Canada Line’s ultimate design capacity.

The SNG will initially have 16 30-metre long trains and 40-metre long platforms, giving it an initial system capacity of only 2,040 passengers per hour per direction (pphpd).

This means that upon opening, the SNG’s maximum capacity will be less than the peak hour capacity of 3,700 pphpd on the 99 B-Line bus service.

Artistic rendering of a Surrey Light Rail station in the middle of a street. (TransLink)

The SNG will have some expansion allowances, as with further investment the platforms can be expanded to 60 metres in length and the train fleet can be doubled to 32 vehicles for double-length trains. However, the ultimate system capacity with these upgrades is just 4,080 pphpd.

In contrast, the Canada Line currently has a peak hour capacity of approximately 6,000 pphpd, and when more trains are added it can reach 12,000 pphpd. With a short 10-metre platform extension from 40 metres to 50 metres to lengthen each train by a car, the ultimate system capacity is established at 15,000 pphpd.

The Expo and Millennium lines have a far greater capacity given that the stations are built with 80-metre long platforms, allowing for longer trains. The current peak hour capacity on the Expo Line is in excess of 15,000 pphpd, and the Expo and Millennium lines each have an ultimate design capacity of approximately 25,000 pphpd.

All three SkyTrain lines also benefit from the use of driverless automation train technology, which allows trains to safely operate at very high frequencies to increase capacity beyond platform-length dependancy. Train systems that require drivers tend to require larger headways.

Much slower and less frequent than SkyTrain

The new LRT will have roughly the same travel time as the existing 96 B-Line bus service that runs along the exact same route the SNG will travel on.

The SNG will have an end-to-end travel time of 27 minutes. By comparison, the recently opened SkyTrain Evergreen extension has a running time of 15 minutes along, even though its route is slightly longer than the proposed LRT line.

While the SNG has a few more stations than the Evergreen extension, the total station dwell time only accounts for 2.5 minutes of the total travel time, according to the Draft Terms Of Reference.

Most of the SNG’s impediments come from its design of being a ground-level train system running through existing streets, and crossing through intersections.

As a result, SNG loses any potential competitive advantage with other modes of transportation from its low speeds due to its complete lack of grade separation, whether it be on an elevated guideway or a tunnel just like SkyTrain.

Additionally, as the train system will run on the street, its ultimate travel speed is restricted to motor vehicle speeds of only 50 km/hr – the local speed limit. On the other hand, SkyTrain has a maximum speed of 80 km/hr.

A comparison of the capable speed and capacity of SkyTrain, light rail transit, and streetcar. (City of Vancouver)

In a car-centric city like Surrey, ridership depends on speed, convenience, and high frequencies, so it is absolutely paramount to ensure that the new transit service is highly competitive to the conveniences of driving. But this will be anything but the case.

Proponents of LRT for Surrey point to other ‘proven’ systems such as Calgary and Seattle as examples to follow, but both systems are turning to grade-separation for their latest projects to address the points of conflict with traffic and increase service reliability.

For instance, much of Calgary’s planned Green Line is underground – particularly in the city’s most urbanized areas. Toronto’s under-construction Eglinton Line has long underground spans while Ottawa’s Confederation Line is fully grade-separated, including a tunnel running under downtown Ottawa.

Furthermore, speed is one of the most vital factors to the Canada Line’s success. A survey conducted in 2011 on the Canada Line’s performance found that the speed of travel was by far the “most liked” aspect of the train service.

Poor reliability; expect many collisions

Around the world, particularly in North America, LRT systems with many at-grade crossings at intersections are notoriously known for having a high collision rate with both pedestrians and vehicles.

While there have been major delays on the SkyTrain system from suicides and accidental falls into the path of an oncoming train at a station platform, there has never been an error with the automation system; the driverless computer system has never been responsible for any death or injury.

With that said, suicides and accidental falls happen on street-level LRT systems as well – these incidents are not exclusive to SkyTrain systems.

Automated trains are known for being extremely safe, with layers of fail-safe systems, while trains manually operated by drivers are subject to the human error of not only the train driver but also pedestrians, cyclists, and the drivers of other vehicles on the road.

And when an accident occurs on the line, the entire system will come to a halt, leading to lengthy delays.

The SNG is particularly vulnerable to collisions given that its route runs along 104 Avenue and King George Boulevard, two of Surrey’s busiest and most important arterial routes. Moreover, the route travels through downtown Surrey, which will only continue to densify – and that comes with more vehicle and pedestrian traffic.

Even TransLink’s recently launched Mobility Pricing Independent Commission acknowledged road congestion in the region’s urban centres, specifically noting Surrey City Centre as one of the hotspots, as a growing problem for street-level transport.

“As the region’s urban centres continue to grow, congestion to, from and within these areas is causing problems for drivers and bus passengers,” reads the Commission’s first report.

Higher construction cost than SkyTrain, but less ridership

Several technology options – varying between SkyTrain, street-level LRT, bus rapid transit, and a combination of modes – were evaluated by TransLink, but somehow the worst of the options was chosen.

According to TransLink’s Surrey Rapid Transit Alternatives Analysis, the RRT 1a option with SkyTrain extended along Fraser Highway from King George Station to Langley and bus rapid transit along the L-shaped route from Newton to Guildford would carry a construction cost $2.22 billion and attract 202,000 daily riders by 2041, including 24,500 new regional daily transit trips.

The system capacity of this SkyTrain extension option can eventually be expanded to 26,000 pphpd to accommodate both projected and unforeseen ridership growth.

Map showing the RRT 1a option with a SkyTrain extension to Langley and bus rapid transit serving Guildford, Surrey City Centre, Newton, and White Rock. Click on the image for an enlarged version. (TransLink)

Conversely, the same study found that the City of Surrey’s preferred LRT 1 option of a street-level LRT system along the L-shaped route from Newton to Guildford would cost $2.18 billion and attract 166,000 daily riders by 2041, including 12,000 new regional daily transit trips.

Even bus rapid transit (BRT) options considered by TransLink would perform better at a lower cost. The BRT 1 option with two bus rapid transit lines connecting Guildford, Newton, White Rock, and Langley would cost $900 million and attract 188,000 daily riders by 2041, including 13,500 new regional daily trips.

The truncated BRT 2 option, which follows the same routes as BRT 1 without reaching South Surrey and White Rock, would cost $770 million and attract 149,000 daily riders by 2041, including 11,500 new regional daily trips.

TransLink’s own analysis even went as far to state the following blunt summary about its technology comparison findings for the Surrey project: “The BRT and RRT-based alternatives were most cost-effective overall in achieving the project objectives due to greater relative benefits (RRT) or lower costs (BRT). LRT 1 and LRT 4 performed the worst in this account, due to higher costs and minimal benefits, respectively.”

Artistic rendering of a Bus Rapid Transit station in Surrey. (SkyTrain For Surrey)

Since this study was created, the cost of the LRT option has risen to at least $2.6 billion. With this figure, the cost is now approaching the same as SkyTrain, but without all of its superior advantages.

As a case in point, the Evergreen extension – the most recent expansion of SkyTrain – is 10.9-kms long, about 500 metres shorter than the SNG. The Evergreen was completed at a cost of $1.4 billion, which included building a challenging 2.2-km long bored tunnel.

For ridership forecasts of the SNG on its own, daily boardings upon opening in 2023 are projected at 36,200, rising to 53,000 by 2030 and 74,000 by 2045.

Bleeding red; operating cost shortfalls for decades

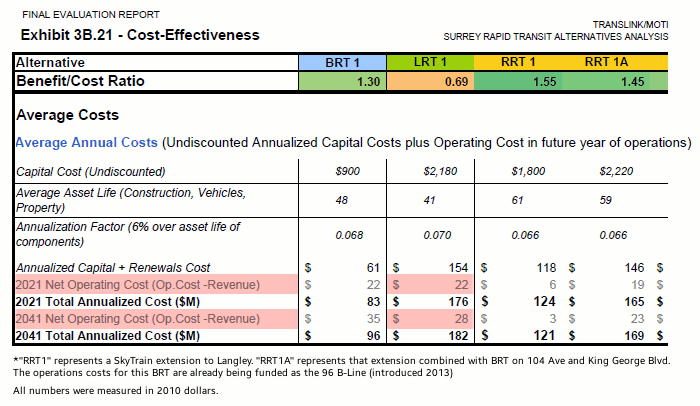

The selected LRT option for both the Newton-Guildford and Langley lines has a cost-benefit ratio of 0.69, which is well below the SkyTrain options (RRT 1 and RRT 1A) and even bus rapid transit. The cost-benefit ratio was also based on a lower construction cost estimate of $2.18 billion, but this has since risen by at least over $500 million.

Cost-benefit analysis performed by TransLink for various alternatives for the Surrey Rapid Transit project. Click here for an enlarged version. (TransLink)

Forecast models by TransLink showed LRT will be unable to recoup its annual operating costs for decades. An annual operating shortfall of $22 million is forecast during the first year, and by 2041 the shortfall will grow to $28 million.

There are higher operating costs with LRT not only due to its use of human drivers but also because of its inability to tap into the economies of scale of a SkyTrain extension. The LRT system requires its own maintenance team, operations and maintenance yard, and its own trains.

As the LRT as designed fails to be a fast, frequent, and convenient rapid transit service, ridership forecasts are lower than the better alternatives.

Lower ridership means less revenue to cover operating costs, and with the system projected to financially operate in the red for many years this could impact TransLink’s future financial capacity to expand transit elsewhere in the south of Fraser.

This LRT was never about mobility and transportation

Light Rail Transit is a popular choice for transit infrastructure and in many ways it can be successful at achieving transit improvement objectives that benefit the region as a whole.

However, this can require design choices that typically involve grade-separation and further increased costs. Surrey’s system offers few of the design features that have made other LRT systems around the world successful and effective at changing travel patterns within a city.

As it stands, the proposed Surrey-Newton-Guildford LRT will deliver only marginal improvements to the existing 96 B-Line, and will do so at extraordinarily high costs.

Although the City of Surrey has suggested that an LRT will fulfill its outcomes of reducing transit commute times and reduced traffic congestion, much of the evidence and information thus far suggests that this system will not deliver on the time savings and transit mode-shift incentives that we should expect from billion-dollar rapid transit projects.

TransLink’s studies have also suggested that there is a poor business case for LRT.

Artistic rendering of a Surrey Light Rail station. (TransLink)

But the City of Surrey’s flagrant economic development ambitions have placed regional transportation and mobility concerns as the project’s second priority. This approach is being made even though real estate development will happen in Surrey regardless of the technology chosen.

“If Surrey and Langley are to reap the billions in economic benefits that a rapid transit system could bring South of Fraser, it must start with an investment in the right transit system – one that is worthwhile for the money that we spend, offers tangible transportation improvements, and is sustainable to operate long-term,” Daryl Dela Cruz, the Founding Director of SkyTrain for Surrey, told Daily Hive.

“Our suggestion for a combination SkyTrain and Bus Rapid Transit system is the option that will deliver the most economic benefits and the best transit improvement outcome for citizens South of Fraser.”

Surrey also asserts that the elevated guideways associated with SkyTrain are visually intrusive and do not align with its ‘urban design principles’. It is worth noting that nearly 15 years ago, the same argument was made by Richmond City Council when it suggested the Canada Line along No. 3 Road should be its own separate street-level LRT system between Bridgeport and Richmond City Centre.

Over the short term, rather than quickly introducing LRT, a more comprehensive and frequent local bus system in Surrey would be the first and most effective step towards improving the city’s public transit system.

Artistic rendering of the light rail transit tracks in the centre of a street in Surrey. (TransLink)

It remains to be seen whether there will be senior government intervention on these LRT plans, just like what happened with the Evergreen extension, which was initially proposed as a LRT project by TransLink and advocated by the municipal governments of the Tri-Cities.

In 2008, the provincial government created its own business case review of the Evergreen Line LRT project, and a recommendation was made in the review’s final report to proceed with SkyTrain given its clear superiority.

The Evergreen extension report said SkyTrain will produce 2.5 times the ridership of LRT, boast an end-to-end travel speed almost twice as fast as LRT, run more frequently, and integrates better into the existing SkyTrain system. More importantly, the $1.4-billion SkyTrain option for the Evergreen extension was only $150 million more than LRT – a relatively minimal cost increase for a significantly better system.

TransLink’s Surrey Rapid Transit Alternatives Analysis report makes similar findings, but this time around the clearly preferred and superior technology is being disregarded by the region’s decision makers.

See also

- Opinion: Traffic gridlock, unreliable trains avoided with Green Line LRT tunnel approval

- Short platforms and trains: Is the SkyTrain Canada Line under-built and near capacity?

- Should the Canada Line be extended to South Richmond and Tsawwassen?

- SkyTrain's Evergreen Extension could be further extended to Port Coquitlam

- Opinion: Why light rail transit is needed on the Arbutus Corridor

- Opinion: Vancouver viaducts demolition to be the worst transportation policy in city's history

Visit the SkyTrain For Surrey campaign website for more information and sign the petition to support the cause.