Opinion: Why light rail transit is needed on the Arbutus Corridor

The landmark decision made by the City of Vancouver to purchase the Arbutus Corridor from Canadian Pacific for the purpose of retaining it as a transportation greenway can be best described as one of the most forward-thinking, long-term transportation policies the municipal government has made in decades.

A light rail or streetcar line, alongside new pedestrian and cycling pathways and green spaces, is envisioned for the 60-foot-wide, nine-kilometre-long railway corridor that traverses from north to south in the city’s Westside neighbourhoods – from Milton Street to 1st Avenue.

On Monday, Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson said the possibility of rail rapid transit on the Corridor is the “core purpose” of the land deal with Canadian Pacific.

“For our transportation future, this is an important corridor and one that we want to preserve,” he said. “As the city grows, there will be undoubtedly be more pressure and need for transportation improvements so we want that option to remain open for the city. It is impossible to acquire a strip of land like this anywhere in the city.”

Securing the Arbutus Corridor for mainly non-developmental purposes enables the Corridor to be used for transportation infrastructure to support Vancouver’s future growth. There are few railway corridors like the Arbutus Corridor in Vancouver, apart from the highly active railways on the Grandview Cut, the south shore of Burrard Inlet, and the north shore of the Fraser River.

The route

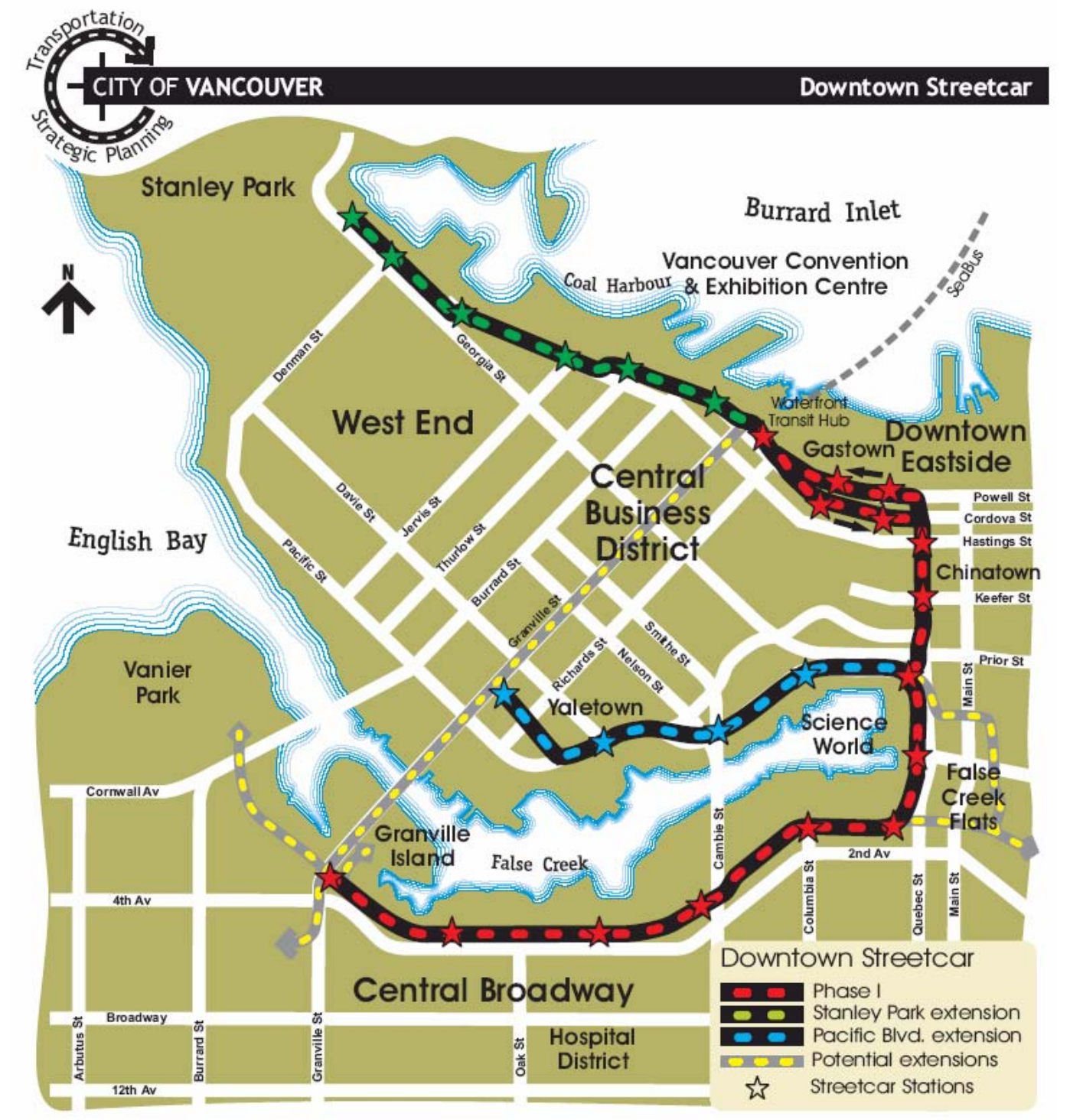

An Arbutus light rail line would likely begin as a natural southern extension of the long-proposed Downtown Vancouver streetcar – from the existing railway right-of-way along South False Creek that starts near Granville Island and ends just west of the Cambie Street Bridge, behind the Canada Line’s Olympic Village Station entrance building. The Arbutus Corridor’s northern tip is just one block away, separated from the start of the South False Creek railway corridor by only a strip mall.

East of the Cambie Street Bridge along 1st Avenue, a wide median was built as a part of the Olympic Village project to accommodate space for a future right-of-way for the streetcar.

The streetcar route then turns north on Quebec Street, with a transfer stop next to SkyTrain’s Main Street-Science World Station. From there, the route continues north and enters Chinatown, where Quebec Street transitions into Columbia Street. The route then turns west onto Powell Street and terminates just outside Waterfront Station while trains returning the opposite direction will travel on Cordova Street.

But this is only accounts for the first phase of the project, which was pegged at $100 million in a 2006 City staff report, including $42.2 million for the construction of infrastructure and $17.3 million to acquire six trains. Further phases, other than the Arbutus Corridor, would bring the streetcar to Stanley Park (via Cordova Street and West Georgia Street), North False Creek (via Pacific Boulevard from Quebec Street), Vanier Park in Kitsilano, the False Creek Flats, and on Granville Street in downtown.

Maintenance facilities and train yards would be located under the Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts or on city-owned property on the False Creek Flats.

Map of the proposed Downtown Vancouver Streetcar with possible extension routes.

Image: City of Vancouver

At the time, City planners were looking to integrate the streetcar network with TransLink’s transit network and fare system. The project would be funded by the City of Vancouver and could be built, designed, and operated as a public-private partnership, similar to the Canada Line.

The first phase running from Granville Island to Waterfront would break even according to the City’s estimates, with a operational cost recovery of between 133% to 144% – with annual operating costs of $3.6 million and annual revenues of between $4.8 million and $5.2 million.

The revival of Vancouver’s streetcar system has been discussed since the mid-1980s and it was a priority for the last Non-Partisan Association (NPA) municipal government led by then-Mayor Sam Sullivan. However, the NPA lost the election to Gregor Robertson’s Vision Vancouver party in the fall of 2008, and the idea has not been a City priority ever since.

Prior to the NPA’s electoral loss, it announced an $8-million plan to operate a 1.8-kilometre-long free demonstration streetcar line, dubbed the Olympic Line, from the Canada Line’s Olympic Village Station to Granville Island. Two new Bombardier streetcar trains, with a carrying capacity of 150 passengers per train, were borrowed from Brussels, Belgium.

Over the 60 day operational period that coincided with the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, the short two-station shuttle line attracted 550,000 passengers or an average of almost 9,200 passengers per day.

In order for an Arbutus rail rapid transit system to be feasible, the Downtown Vancouver streetcar would have to be built first to establish the supporting ridership network and infrastructure required for the long extension.

Trains running on the nine-kilometre-long Arbutus Corridor, running alongside almost all of Arbutus Street, would have a right-of-way that would not be impacted by most road traffic – except at where the right-of-way crosses east-to-west streets. But for the most part, there are few streets that cross into the right-of-way, particularly from West 16th Avenue all the way to Southwest Marine Drive and the Fraser River.

With only 10 street crossings along a 55 block stretch of the Corridor, a rail transit system would be relatively reliable and quick. Construction costs could also be relatively low with the use of an existing railway right-of-way.

Satellite view of the Arbutus Corridor with few street crossings from West 16th Avenue towards West 33rd Avenue.

Image: Google Maps Satellite View

In contrast, the option of building the Broadway rapid transit extension as a 12-kilometre-long, street-level light rail system down the middle of Broadway and West 10th Avenue from Commercial Street to UBC would pass through as many as 67 intersections.

From the end of the Arbutus Corridor, the route would likely continue on to the Canada Line’s Marine Drive Station to create a major transfer connection or across the Fraser River as a secondary rail transit crossing serving Richmond and Vancouver International Airport (YVR).

Second to the Canada Line

It was fifteen years ago that RAVCO, the now-defunct subsidiary of TransLink created to lead the planning of the Canada Line, considered using the Arbutus Corridor for the SkyTrain extension from downtown Vancouver to YVR and Richmond.

A decision was eventually made to build the extension along the Cambie Street corridor as the route had a significantly greater ridership potential. It is situated near the geographical centre of Vancouver, which better serves both Eastside and Westside residents for those transferring from bus or other modes, and is a shorter and more direct route compared to the winding Arbutus Corridor option.

According to planning documents, end to end travel time on the Arbutus Corridor route option was 35 minutes whereas the Cambie Corridor route option was significantly shorter at 25 minutes.

As well, the Cambie Street route would serve a far greater number of major employment centres, such as the offices on Central Broadway, the Vancouver General Hospital campus, Vancouver City Hall, and Oakridge Centre.

There are also more sites along the Cambie Corridor that are suitable for redevelopment to not only help support ridership growth over the long term but also create sustainable population and employment growth. Today, major redevelopment projects are planned for Oakridge Centre, Vancouver Coastal Health’s Pearson Dogwood lands, and the RCMP’s former headquarters near 33rd Avenue.

Furthermore, the Cambie Street corridor is in the midst of a transformation: Single-family homes along street south of King Edward Avenue are being demolished and replaced with low-rise and mid-rise residential projects. There are currently at least 15 such projects planned or approved for this stretch of the Corridor.

Comparison of Canada Line route options: Arbutus Street vs. Cambie Street.

Image: TransLink

Image: TransLink

While the correct decision was made to build Vancouver’s primary north-south rail rapid transit backbone along Cambie Street, there is still a future need to reserve the Arbutus Corridor for the a secondary north-south rail transit line – a “relief line”, a term used in other cities, to the Canada Line four kilometres away.

Capacity issues on the Canada Line will likely arise in 20 to 30 years due to the system’s short platforms after all built-in methods of increasing capacity are exhausted. In less than seven years, the system has already reached more than two-thirds of its ultimate 15,000 passengers per hour per direction (pphpd) capacity.

Platforms are built to lengths of at least 40 metres, with the capability to extend all station lengths to up to 50 metres to accommodate slightly longer trains. More trains could also be added to increase the frequency of operations, thus increasing capacity, but there is a limit for how many trains the system can operate at any one time.

Ridership on the Canada Line will soar when the SkyTrain Millennium Line is extended along Broadway to Arbutus, with passengers transferring between lines at Broadway-City Hall Station. The Arbutus Line would also connect to the Millennium Line with a transfer point at Arbutus Street and Broadway.

If built, an Arbutus light rail transit system will become the main north-east rail transit route for many Vancouver Westside transit users, effectively freeing up capacity on the Canada Line and significantly broadening the region’s transit network. The larger the region’s rail rapid transit network becomes, the more attractive and feasible public transit becomes as the transportation mode of choice.

Currently, the Arbutus Corridor is served by the No. 16 trolley bus route – the fifth best performing bus route in the entire region in terms of ridership.

TransLink’s most recent Bus Service Performance Review indicates that the bus route sees over seven million boardings annually, which represents an average of approximately 21,000 boardings per day. Its average capacity utilization is 230%, the highest of all bus routes.

Curbing the expectations of Arbutus Corridor residents

The extension of the SkyTrain Millennium Line to Arbutus, and ultimately to the University of British Columbia campus, is the City of Vancouver’s main public transportation priority. Regionally, there is also Surrey’s light rail ambitions to consider.

An Arbutus light rail system will not be seriously considered until these two regional priorities are completed. And that does not account for other possible rail rapid transit projects, including a line running along Hastings Street from downtown Vancouver or even a rail connection between downtown Vancouver and the North Shore.

The apparent need for light rail on the Arbutus Corridor will likely not materialize until the 2030s. In the meantime, the municipal government plans to convert the Arbutus Corridor into a greenway with cycling and pedestrian pathways and space for legal community gardens. All of Canadian Pacific’s freight railway infrastructure along the Corridor will be removed in two years and a public consultation phase to determine the future of the Corridor will be completed before the end of the decade.

Given that the City acquired the Corridor for the primary purpose of preserving it for rail rapid transit, the proposed $30-million greenway must be designed in a way that does not require the removal or any significant change in the pathways that users and nearby residents become accustomed to.

Any consultation process must clearly indicate the future use of the Corridor for rail rapid transit as a means of curbing local neighbourhood opposition to a light rail system.

Trains have long been a part of the Arbutus Corridor’s history: Freight trains and even streetcars have used the Arbutus Corridor for a century, until 2001 when the last train departed the Molson Brewery. Residents living along the Arbutus Corridor need to be reminded of this.