Three weeks after revealing the proposed official venue concept plan for the potential Vancouver 2030 Olympic Winter Games bid, the Four Host First Nations and the Canadian Olympic Committee (COC) have provided a preliminary financial estimate for executing the repeat Games.

The local organizing committee (OCOG) costs — the second iteration of an entity just like VANOC, but led by the Indigenous community — are estimated at between $2.4 billion and $2.8 billion, which covers the cost of planning, organizing, and executing the operations. The 2030 OCOG costs will be 100% privately funded through domestic sponsorship, a share of the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) broadcast and sponsor revenues, ticketing, merchandise, and other sources.

For comparison, VANOC’s 2010 operating budget was $1.9 billion, with $659 million covered by the IOC, $731 million from domestic sponsorship, and $270 million from licensing and merchandising. The federal and provincial governments also contributed $188 million to VANOC’s operating costs. When VANOC was dissolved in 2013, financial statements show it balanced its books.

- You might also like:

- The official proposed venues for Vancouver’s second Olympics in 2030

- Hastings Park and PNE eyed for Vancouver 2030 "Olympic Park" transformation

- Big Air at Hastings Park for 2030 Olympics? A throwback to the PNE's ski jump (PHOTOS)

- Vancouver City Council says no to public vote on 2030 Olympic bid

- Vancouver 2030 Olympic Village in a First Nations development a possibility

- It will cost up to $260 million to host the 2026 FIFA World Cup in Vancouver

Like 2010, the construction and security budgets are calculated separately. The COC estimates between $1 billion and $1.2 billion in public funding will be needed to cover these non-OCOG costs, including $299 million to $375 million for renewing the venues for another 20 years, $165 million to $267 million to build a First Nations affordable and market housing legacy incorporated into the Olympic Villages, and $560 million to $583 million for security.

In contrast, the BC provincial government estimates Vancouver’s confirmed role as a co-host city for the 2026 FIFA World Cup will carry a full cost of $240 million to $260 million.

The 2030 venue costs — 54% of 2010’s costs — will largely go towards “refreshing” the venues used for 2010 for another 20 years, effectively extending the lifespan of the existing facilities. As announced last month, no new venues are planned for the 2030 Games.

It should also be emphasized that the venue costs include a significant 35% contingency for unexpected costs, with 25% towards design contingency and 10% for construction contingency. This will particularly help mitigate inflation over the coming years.

The provided cost for the Olympic Villages — three villages located in Vancouver, Whistler, and Sun Peaks — is not the actual cost of building these residential developments, but rather the cost of leveraging the Games and projects to accelerate much-needed affordable housing as a post-Games legacy. It is anticipated the 2030 Games will provide over 1,000 new homes, with the Vancouver village eyed for either the Jericho Lands or Heather Lands, which are both First Nations-owned and led projects.

As for the big-budget item of security, the estimated cost for 2030 is about 53% of the 2010 costs of $1.1 billion (adjusted to 2022 dollars). The COC explained that after 2010, the federal government, law enforcement, and intelligence agencies developed a completely new “intelligence-led” model of planning and providing security for large events. New technology developed over the past decade also allows for the more efficient deployment of security. This is also evident by the significantly lower security costs for the much larger Toronto 2015 Pan American Games and Canada’s hosting of the 2018 G7 Summit, which were about 25% to 33% of the 2010 Olympics and 2010 G7 Summit costs.

The COC estimates that for every public dollar spent by the BC provincial and municipal governments on the 2030 Games, about $5 or $6 will come into the region from outside sources such as the federal government and private sources — but not including additional economic impacts from tourism, job creation, and provincial and local government tax revenues.

These costs also do not include potential federal, provincial, and municipal governments’ additional investments to leverage the Games further, such as expediting the SkyTrain Millennium Line extension to the University of British Columbia and other transportation infrastructure projects in time for the 2030 Games. Examples of such additional leverage investments made in time for the 2010 Games include the SkyTrain Canada Line and the Vancouver Convention Centre’s West Building.

“We know the public is eager to hear what the cost of the 2030 Games will be, and I hope that the financial estimates are reassuring that it is not only feasible to host these Games, but it is beneficial to all of our communities,” said Wayne Sparrow, Chief of the Musqueam Indian Band, in a statement.

The COC is currently fully funding the process of examining the feasibility of bidding for the 2030 Games. Over the coming months, the respective councils of the Four Host First Nations — Musqueam, Squamish, Tsleil-Waututh, and Lilwat — and the cities of Vancouver and Whistler will decide on whether to proceed with the bid. If all six councils provide the green light, the COC will advance the bid to the international bidding stage by December 2022, when the IOC is expected to reach the “targeted dialogue” stage of selecting the 2030 host city. The IOC is expected to make its decision on the 2030 host city during its upcoming session in Mumbai in May 2023.

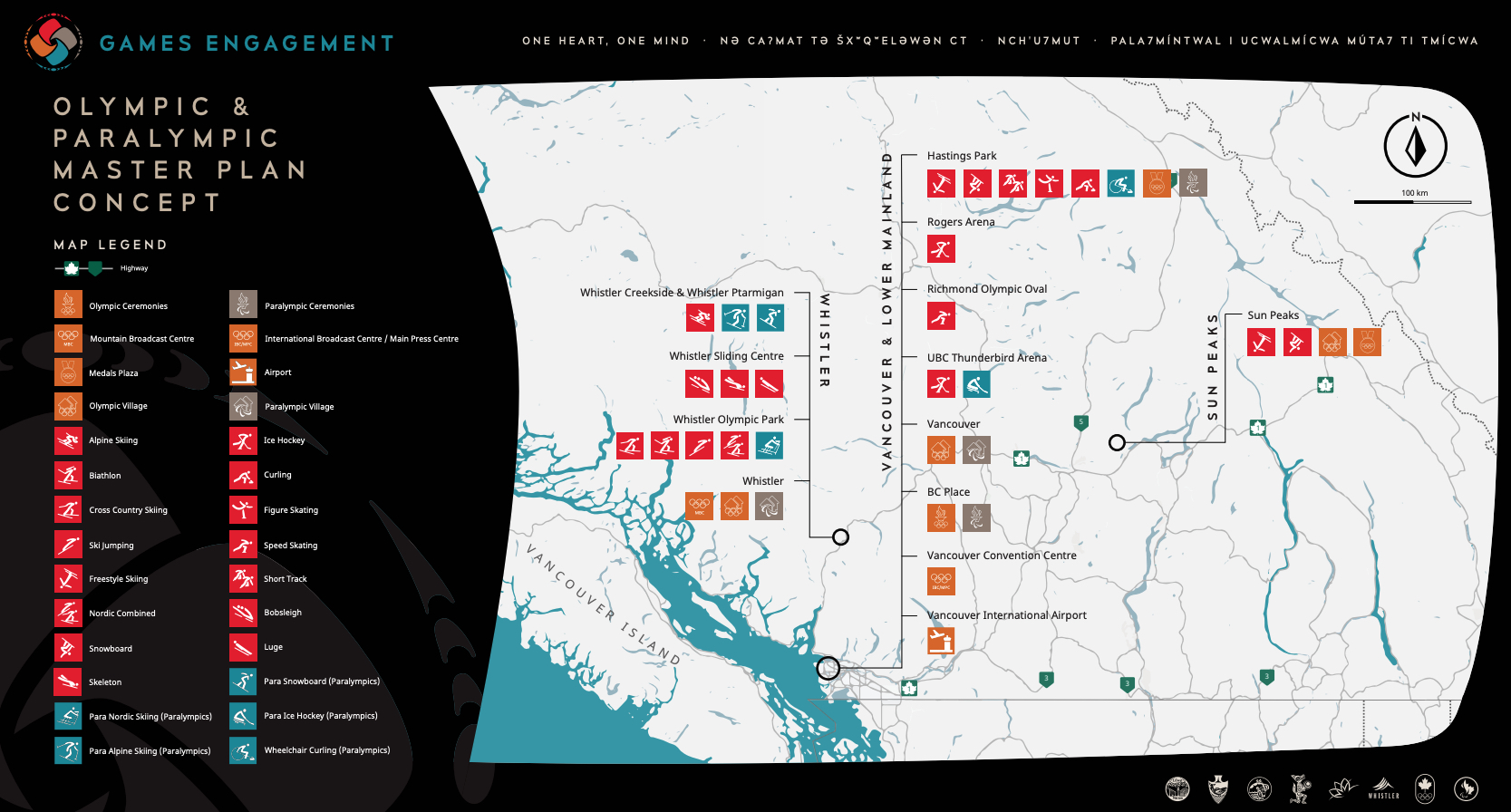

Map showing the proposed venue concept plan for the BC 2030 Olympics. Click on the image for an expanded version. (Canadian Olympic Committee)

- You might also like:

- The official proposed venues for Vancouver’s second Olympics in 2030

- Hastings Park and PNE eyed for Vancouver 2030 "Olympic Park" transformation

- Big Air at Hastings Park for 2030 Olympics? A throwback to the PNE's ski jump (PHOTOS)

- Vancouver City Council says no to public vote on 2030 Olympic bid

- Vancouver 2030 Olympic Village in a First Nations development a possibility

- It will cost up to $260 million to host the 2026 FIFA World Cup in Vancouver