Opinion: Air of toxic skepticism in West Vancouver ahead of B-Line decision

If the North Shore B-Line runs through deep into the community, bus-only lanes and turning-lanes are implemented, and 25 of the 800 on-street parking spots over a 20 city block stretch are removed, West Vancouver as we know it will end.

No, seriously — that is the grim picture being aggressively painted by a vocal group of businesses and residents against a bus going through their neighbourhood.

See also

- Opinion: North Shore B-Line is the precursor to future rail transit

- West Vancouver businesses against new bus-only lanes for North Shore B-Line

- TransLink releases B-Line road design changes for North Vancouver

- West Vancouver slated to decide on B-Line bus-only lanes in March

- West Vancouver's population has been falling for the last 5 years

From personal attacks against local leaders to even a protest last month that resembled one of the many anti-pipeline marches that have been held in downtown Vancouver, the whole debate over the B-Line in West Vancouver — which only started late last fall — has gone to absurd lengths. There has not been such an intense campaign of misinformation on an urban issue in the region since the transit plebiscite.

Most recently, over the weekend, a “movie trailer” released by opponents provided a “preview” ahead of the final decision West Vancouver district council is expected to make on Monday.

The Mayor – The Movie 🎥 pic.twitter.com/tU1kx4eH6Y

— CogentthoughtsWV (@CogentthoughtsW) March 2, 2019

Let me remind you once more that this is over a bus.

But at its very core, this is all about trying to curb any attempt at change — an attempt to keep things as they are now, and keep outsiders out.

As with most public consultations on matters of development and transportation, there is a very apparent generational divide, with those opposed against progress and improvements mainly being the older generations. Younger generations, especially in a place like Metro Vancouver where the cost of living has reached unattainable heights, are far too busy making ends meet to contribute their voice to matters that most impact them.

Here is a case in point: “West Van is a lovely place to visit, even if only a lucky few can afford to live there. We should all join the effort to help preserve its Shangri La-like state. The B-Line bus is a rude intruder with GHGs and muddy boots. There are no B-Line buses in Shangri-La.”

Those were the actual comments made by Paul Sullivan, a North Shore resident and former Vancouver Sun editor, in his recent op-ed published in the North Shore News.

It harkens back a similar infamous statement made by a Kerrisdale resident nearly two decades ago when TransLink was considering the Canada Line’s route along the Arbutus Corridor.

“We are the people that live in your neighbourhood. We are dentists, doctors, lawyers, professionals, and CEOs of companies. We are the creme de la creme in Vancouver. We live in a very expensive neighbourhood and we’re well educated and well informed. And that’s what we intend to be,” Pamela Sauder told Vancouver City Council in 2000.

The reality is bus-only lanes through West Vancouver reaching Dundarave are meant to increase the reliability and speed of both the existing Blue Bus routes that run along Marine Drive and the future B-Line from Dundarave to Phibbs Exchange. It is not just for the B-Line, nor is West Vancouver the only municipality in the region receiving street design changes to accommodate new B-Line routes.

Depiction of bus-only lanes and changes at intersections with new turning lanes for the North Shore B-Line in West Vancouver. (District of West Vancouver)

Typical cross section: Ambleside. (TransLink)

The value of speed should never be underestimated for getting people out of their cars and into transit, and a route that reaches Dundarave creates a backbone bus route in the North Shore that touches all major destinations and points to make the B-Line far more usable. East-West travel in the North Shore would be significantly enhanced by the full-length B-Line route, which has stops within a short walking distance from 25% of North Shore residents, 40% of North Shore jobs, and 35% of planned North Shore growth.

But it is this very idea of improved connectivity to the ‘outside world’, beyond West Vancouver, that scares these protesters.

In a non-selfish, non-entitled reality, this B-Line is representative of the first dose of medicine that this community is in dire need of. West Vancouver’s population actually fell by about 5% between 2011 and 2016 — from about 43,000 residents to 41,000 residents, according to provincial government statistics. The losses are from an aging population and unaffordable housing — things that inhibit a healthy local economy.

A fast, frequent, and convenient B-Line will provide West Vancouver businesses struggling to find workers with access to a larger labour market pool, especially for filling lower wage positions in retail and restaurants.

Even West Vancouver’s municipal government depends on a workforce that largely lives outside of its municipal boundaries. The district says 78% of its employees — including library, parks and recreation, fire and rescue, and police — commute to West Vancouver from other municipalities.

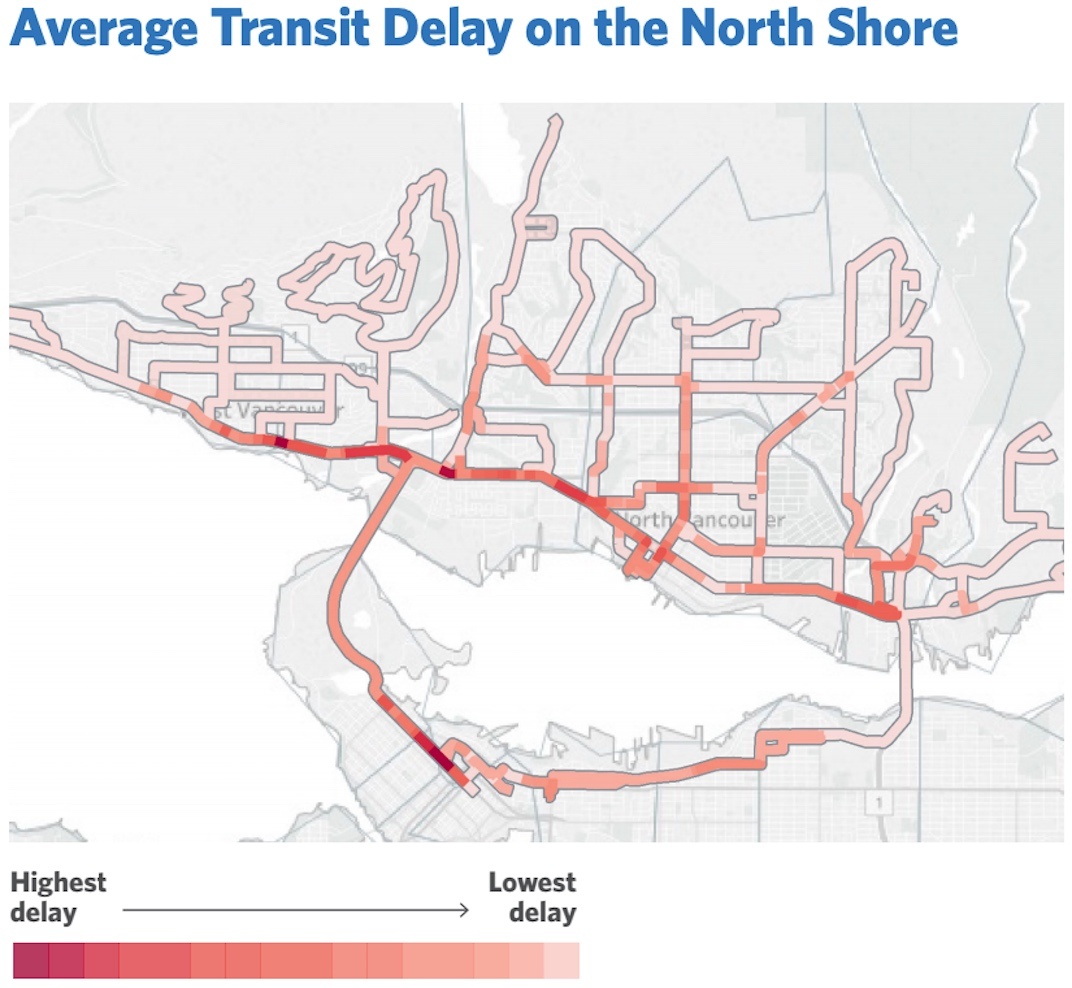

Map showing average transit delays on the North Shore. (District of West Vancouver)

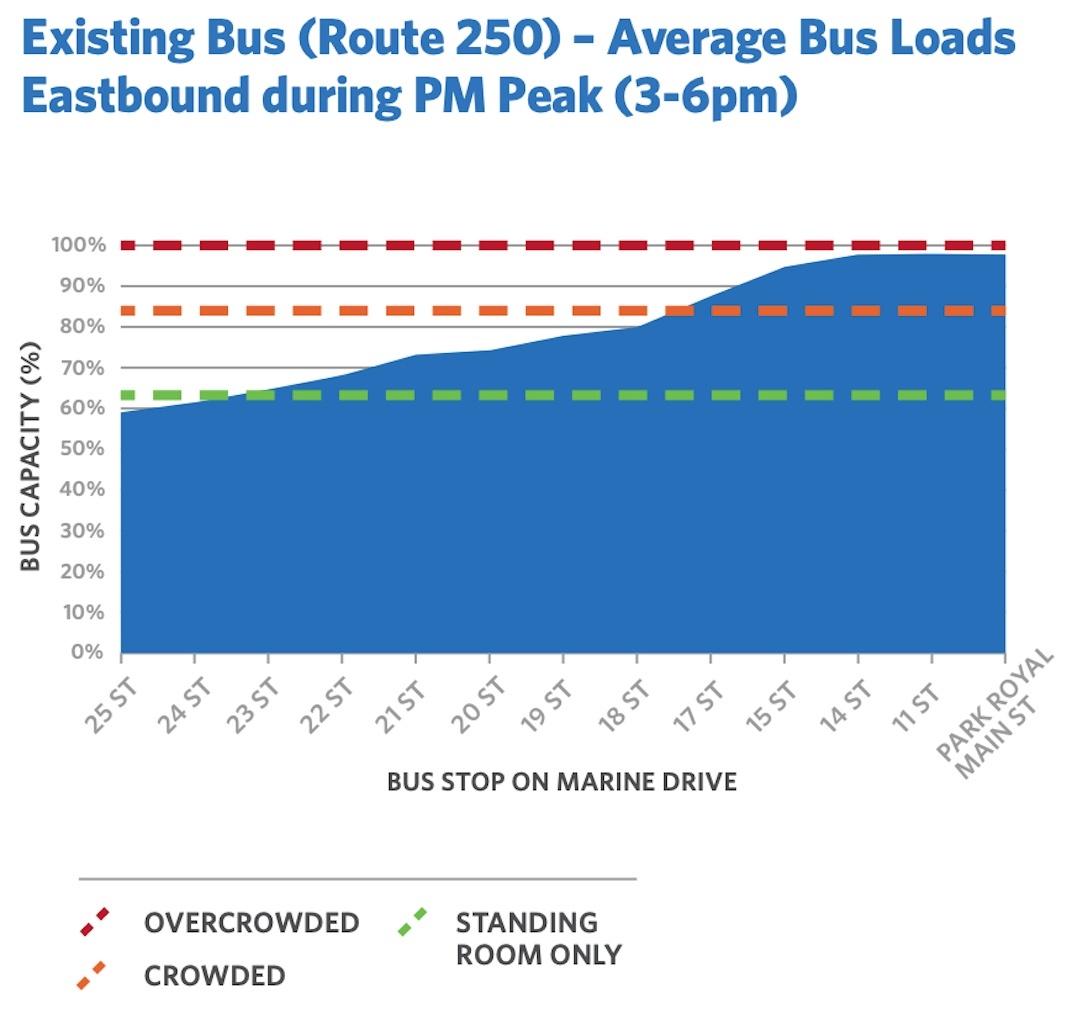

Example of passenger volumes on a busy transit bus in West Vancouver. (District of West Vancouver)

The demand for improved transit clearly exists, with recent TransLink data showing a bus ridership of over 8,000 daily passengers between Dundarave and Ambleside and over 11,000 passengers at Park Royal.

“As the cost of living in West Vancouver continues to increase, ridership demand for people who do not live in, but work or go to school in our community, is rising. On some West Vancouver bus routes, demand already exceeds capacity,” reads a public engagement material by the district.

And all of the region’s past and existing B-Line routes have provided retail areas located around the stops with a boost in business; there is no reason to think the same boost will not materialize for the businesses in Ambleside and Dundarave, which have been struggling to survive amidst an expanding Park Royal shopping centre.

Due to the kerfuffle, the emerging discussions within the district on proceeding with the new bus route deal with largely truncating the B-Line in West Vancouver — ending at Park Royal instead of continuing for three more stops west to terminate at Dundarave. The real benefits of the service would be lost not just within West Vancouver but the entire North Shore.

“The problem of traffic congestion is only going to get worse in years to come. We must remain willing to consider all strategies to deal with this problem,” said West Vancouver Mayor Mary-Ann Booth in a statement last week.

“West Vancouver residents have made significant financial contributions to TransLink over the years, but received comparatively little in terms of new or improved services… Former mayor Michael Smith played a prominent role in ensuring this project was included in Phase 1 of the Mayors’ Council’s 10-year plan.”

North Shore B-Line roadway changes through North Vancouver. (TransLink)

TransLink plans on launching the North Shore B-Line this fall, along with two other B-Line routes elsewhere in the region along 41st Avenue in Vancouver (between UBC and Joyce-Collingwood Station) and Lougheed Highway (between Coquitlam Central Station and Maple Ridge).

If the District of West Vancouver approves its bus route segment, the West Vancouver portion of the North Shore B-Line will be implemented in 2020.

See also

- Opinion: North Shore B-Line is the precursor to future rail transit

- West Vancouver businesses against new bus-only lanes for North Shore B-Line

- TransLink releases B-Line road design changes for North Vancouver

- West Vancouver slated to decide on B-Line bus-only lanes in March

- West Vancouver's population has been falling for the last 5 years