12 things proposed for the Vancouver 2010 Olympics that didn't happen

Vancouver’s journey to hosting the 2010 Olympic Winter Games began a decade after it held Expo ’86, when a not-for-profit group began vying for the domestic rights — against Calgary and Quebec City — to submit a bid to the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

Of course, the Canadian Olympic Committee chose Vancouver over Calgary and Quebec City, and ultimately the IOC chose Canada’s bid over Pyeongchang and Salzburg.

- See also:

Over the almost 15-year timeframe of bidding and planning for 2010, numerous ideas on how the Games could be staged were contemplated to some degree, ranging from varying locations for venues, transportation infrastructure options, and the nitty gritty details of the Olympic Ceremonies. Many of these ideas did not reach the finish line.

Here are 12 things that were proposed but didn’t happen for the 21st Olympic Winter Games:

1. Speed skating oval was originally planned for SFU Burnaby

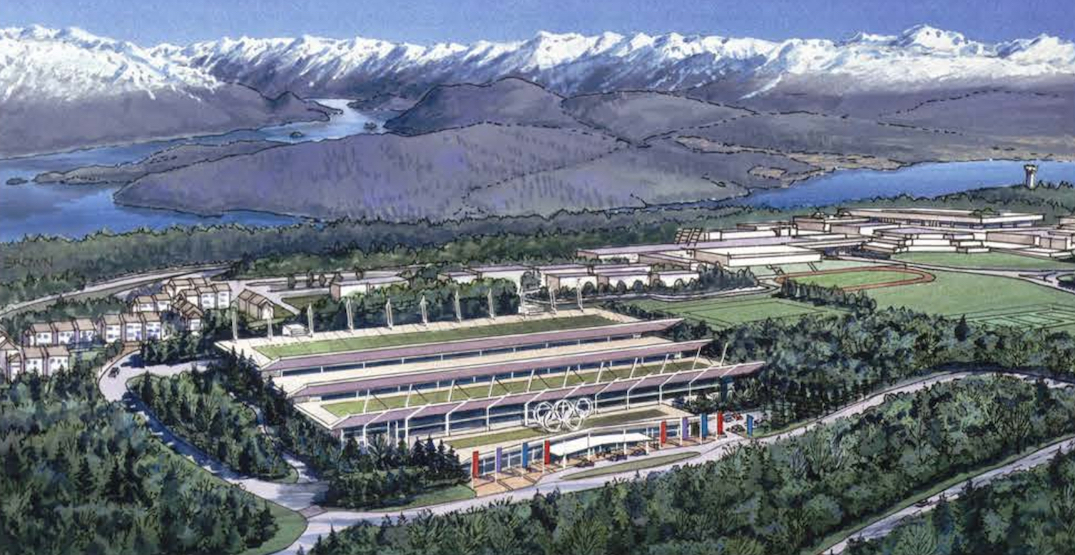

During the bid, plans called for a new 220,000-sq-ft speed skating oval to be built atop Burnaby Mountain as a recreational legacy for the Simon Fraser University (SFU) campus.

But shortly after the IOC’s host city decision, VANOC took a closer look at the oval plans for SFU and determined construction costs would be higher than the allocated budget of $64 million, partially due to the unique geotechnical challenges of the hillside mountaintop location.

Artistic rendering of the Olympic Speed Skating Oval at Simon Fraser University’s Burnaby Mountain campus. (Vancouver 2010 Bid Committee)

The University of British Columbia (UBC) and the City of Richmond began creating their own competing alternative plans. UBC proposed an expanded Thunderbird Sports Centre complex to include a speed skating oval, as part of VANOC’s confirmed plans to build a secondary ice hockey arena on the campus.

In September 2004, VANOC decided to proceed with Richmond’s proposal of a 360,000-sq-ft oval on city-owned land used as a trailer park. The organizing committee’s contribution towards construction was limited to $60 million, while the municipal government covered the balance of the total $178-million cost through casino and area development revenues.

The Burnaby Mountain site that was previously dedicated for the oval is now slated to become a future expansion of the SFU campus.

2. Vancouver Olympic Village at UBC

Early on in the domestic bid stage, the area south of the intersection of Wesbrook Mall and West 16th Avenue at UBC was considered as the site of the Vancouver Olympic Village.

This UBC option was later abandoned in favour of placing the accommodations of nearly 3,000 athletes and officials on city-owned waterfront land in Southeast False Creek (SEFC), with an initial concept situating the Olympic Village immediately east of the Cambie Street Bridge. But due to bridge noise and security concerns, a decision was made to place the Olympic Village on the eastern parcel closer to Quebec Street and Science World.

UBC Stadium Neighbourhood area in south campus, with Wesbrook Village located nearby. (UBC)

The UBC site became Wesbrook Village (Wesbrook Place), which serves to add to the university’s endowment and provide new housing options. The first phase of the new neighbourhood, adding to the university’s endowment, was completed in the late 2000s, and upon full buildout there will be over 12,000 residents in six million sq. ft. of residential space.

The area also has a 110,000-sq-ft retail village anchored by Save-On-Foods, a new building for University Hill Secondary School, a new community centre, and parks and open space.

The Southeast False Creek master plan, including the Olympic Village. (City of Vancouver)

The SEFC site immediately east of the Cambie Street Bridge remains under city ownership and undeveloped, used as a gravel pit parking lot for Vancouver Police and TELUS vehicles, and temporary modular housing. The city has long-term plans to develop the site into new housing with a large waterfront public park.

3. International Broadcast Centre in Richmond

In VANOC’s bid book to the IOC, the International Broadcast Centre (IBC) — one of the two major media facilities for each Olympics — was envisioned as a $30-million temporary trailer park located on the Garden City Lands in Richmond. The IBC is the location where dozens of worldwide Olympic television rights holders set up their basecamp of operations, such as studios and office facilities.

The Main Press Centre was slated within Vancouver Convention Centre’s (VEC) space inside Canada Place, now known as the East Building of the VEC.

Garden City Lands Park. (City of Richmond)

After the bid victory, the provincial government decided to proceed with the project to build the West Building of the Vancouver Convention Centre, at a cost of $883 million, in time for the Olympics. It would serve as the IBC for broadcasters and allow for an amalgamated media hub that would be known as the Main Media Centre.

While a temporary IBC in Richmond was feasible, it was far from ideal given the operational efficiencies and the lacklustre location. The 134-acre Garden City Lands, located east of Lansdowne Centre and the Kwantlen Polytechnic University, have since been turned into a city park.

4. Drilling through Grouse Mountain for a new highway to Whistler

In the early 2000s, the provincial government considered a range of varying options to provide a reliable transportation link between Vancouver and Whistler.

The existing narrow, two-lane Sea-to-Sky Highway was more than just inadequate, with not only a travel time often over two hours but its frequency of accidents — an average of 300 accidents per year prior to the completion of highway upgrades in late 2009.

The most fanciful of the options was boring an eight-km-long tunnel through Grouse Mountain as part of a new secondary highway route that would join up with the Sea-to-Sky Highway near Squamish. The estimated cost at the time was over $6 billion.

Another option was a new secondary highway route from Coquitlam, on the route of Pipeline Road and along the eastern edge of Coquitlam Lake, at a cost $4 billion.

There was also a $4.5-billion option of a high-speed rail line on the Sea-to-Sky Corridor.

For the options of improving the existing Sea-to-Sky Highway, the costs ranged between over $300 million and $2 billion, depending on the scope of work, such as creating a new four-lane standard for the entire route from Horseshoe Bay to Whistler.

An alternative idea, accompanied with a modest upgrade of the Sea-to-Sky Highway, was to run passenger ferries from Bridgeport in North Richmond and Canada Place in downtown Vancouver to Squamish, where spectators would then board buses for their remaining journey to Whistler.

In the end, the provincial government decided to proceed with a $600-million option that created a new overland route near Horseshoe Bay, created a four-lane standard in certain sections, widened the width of the lanes, reduced curves, and made spot safety improvements.

The upgraded Sea-to-Sky Highway near Furry Creek. (Shutterstock)

5. Men’s Ice Hockey and Figure Skating finals at BC Place Stadium

The bid committee’s final presentation to the IOC in Lausanne announced a plan to host the Men’s Ice Hockey gold medal and Figure Skating final events inside BC Place Stadium, the venue for the Olympic Opening and Closing Ceremonies, and the nightly Victory Ceremonies and concerts.

With 60,000 fixed seats at the time, BC Place Stadium, as a football and soccer stadium, was far larger than the primary ice hockey venue of GM Place (19,000 seats) and the primary figure skating venue of Pacific Coliseum (15,000 seats).

But there were certainly major logistical issues with the idea, primarily with ice quality and particularly its impact on preparations for the Opening and Closing Ceremonies.

For the Victory Ceremonies, the stadium was divided into two areas by a curtain, utilizing a 30,000-seat venue capacity. Final rehearsals for the Closing Ceremony were also conducted during the Games’ daytime.

Precedent was previously set by Atlanta 1996, when it converted the now-demolished, 80,000-seat Georgia Dome into two sports venues. The stadium was divided into two with a curtain and temporary in-field grandstands, with one half used for basketball and the other half for gymnastics. Each half’s capacity was about 40,000 seats.

In 2014, a temporary ice rink was built inside BC Place Stadium to allow it to host the NHL Heritage Classic between the Vancouver Canucks and Ottawa Senators. While it was a novel experience, there was a mixed reception partially due to the poor sightlines.

BC Place Stadium during the 2014 NHL Heritage Classic. (Pavco)

6. Olympic Cauldron on BC Place Stadium’s roof rim

Also during the final bid presentation to the IOC, the bid committee revealed their idea of turning the concrete rim of the roof of BC Place Stadium into a ginormous Olympic Cauldron. Animation of the surreal-sized Olympic Cauldron was included in the presentation’s video.

Artistic rendering of the roofline of BC Place Stadium turned into the Olympic cauldron. (Vancouver 2010 Bid Committee)

While they were still able to launch fireworks from this concrete rim during both the Olympic Opening and Closing Ceremonies, such an installation would have been highly cost prohibitive to construct and operate, given the volume of natural gas required. And undoubtedly, there would have been safety concerns for the ring of fire on the perimeter of an air-supported roof.

VANOC went on to build three Olympic Cauldrons: a temporary ceremonial prop Olympic Cauldron inside BC Place Stadium; a permanent legacy replica Olympic Cauldron at Jack Poole Plaza visible to the public; and a permanent community Olympic Cauldron at Whistler Medals Plaza. The Olympic Cauldron installation at Jack Poole Plaza was achieved through a late $3-million contribution from Terasen Gas, now known as FortisBC.

7. Whistler Medals Plaza was cancelled to cut costs

The onslaught of the 2008 recession forced VANOC to make a number of cutbacks, including its plans for nightly Victory Ceremonies and concerts at Whistler Medals Plaza, which had a capacity of 8,000 spectators.

To reduce costs, athletes at Whistler sports events would receive their medals at the venues instead. But there were no plans to cancel the Vancouver Victory Ceremonies held inside BC Place Stadium.

However, there was pushback to this idea from the IOC, municipality, and the public, given that an outdoor Victory Ceremonies are a long-standing Winter Games tradition and would heavily add to Whistler Village’s Olympic atmosphere.

In Spring 2009, VANOC revived its plans for $13 million of programming for the Whistler Victory Ceremonies, after the scope was reduced to cut down on costs sufficiently, such as busing 400 workers instead of providing accommodations in Whistler and reducing the venue’s media facilities.

Whistler Medals Plaza during the Olympics. (Kyle Lane / Flickr)

8. Cutback on Olympic decorations

VANOC’s “Look of the Games” budget was one of the first items that was severely slashed as a result of the 2008 recession.

Approximately $30 million was cut back on the original scope of the Vancouver 2010-branded decorations and installations, which create a memorable visual experience for local residents, athletes, visitors, and the international broadcast audience. This included the elimination of some permanent legacy installations.

Potential Look of the Games concepts included not only many more banners to enhance the exterior of venues and the public realm, but also Olympic ring installations in the waters of False Creek, the peak of Grouse Mountain (similar to Salt Lake City 2002), and Shangri-La Vancouver, the city’s tallest building.

Olympic rings atop Grouse Mountain and in the waters of False Creek were some of the original “Look of the Games” concepts envisioned for Vancouver 2010. (VANOC)

Some visitors and international media at the time commented Vancouver lacked the unique Olympic look host cities are known for. But VANOC still performed essential Look Treatments to all nine competition and 10 non-competition venues, including 63 kms of 2010-branded security perimeter fence fabric and 12 venue towers.

The most visible Look of the Games public realm treatment were 6,000 Olympic street banners at a cost of $650,000, and the two sets of giant LED-illuminated Olympic rings installed in the waters of Coal Harbour and the entrance into Vancouver International Airport. Both ring installations cost $4.5 million combined, and would glow yellow on the days Canadian athletes secured a gold medal.

Some of VANOC’s leftover wood and concrete venue pillar signs have been reused as directional signage by the Vancouver Park Board and the PNE.

Similar cutbacks to the scope of the Look of the Games were also made to Rio de Janeiro 2016 due to the difficulty financial and economic realities of Brazil and the host city.

Artistic rendering of Vancouver 2010’s Look of the Games on Robson Street. (VANOC)

Artistic rendering of Vancouver 2010’s Look of the Games at Whistler. (VANOC)

Olympic rings atop Shangri-La Hotel, Vancouver’s tallest building, and branded decorations were some of the original ‘Look of the Games’ concepts envisioned for Vancouver 2010. (VANOC)

Artistic rendering of Vancouver 2010’s Look of the Games at the Port of Vancouver. (VANOC)

9. Cirque du Soleil as the Ceremonies production team

Cirque du Soleil had been favoured to produce the Olympic Opening and Closing Ceremonies. VANOC had favoured the world-renowned Canadian entertainment company — it seemed like a natural fit given the company’s experience and guarantee of high-quality productions.

But VANOC took issue with Cirque co-founder Guy Laliberte’s inflexible creative vision of create an Opening Ceremony theme on the world’s water crisis, ignoring the organizing committee’s desire of having a production with a theme that directly celebrates Canadian culture.

“I think he saw the ceremonies as a way to tell a story that he felt needed telling,” said VANOC CEO John Furlong in his memoir. “No doubt it would have been beautiful, but it bothered me that Cirque never seemed to want to talk about or acknowledge the vision we had.”

Cirque later withdrew its bid to produce the shows, citing the company did not think it had the time devote itself fully because of its numerous other productions worldwide.

VANOC went on to select David Atkins Enterprises (DAE), the Australian-based production team behind the ceremonies of the Sydney 2000 Summer Games and the Doha 2006 Asian Games. They operated with a budget of $48.5 million, including a late $8.5 million budget increase in 2009 to fund the cost of the large circular fabrics suspended from BC Place Stadium’s roof. These were integral to the show, as they were used as projection backdrops. Without this added investment, DAE said the show would immensely suffer and risk Canada’s global reputation.

Five years later, Cirque produced the Opening Ceremony of the Toronto 2015 Pan Am Games, and was recognized as an official sponsor.

10. Celine Dion performing “O Canada”

Celine Dion had originally been lined up to perform the Canadian national anthem during the Olympic Opening Ceremony, but she rejected the role, as she was trying to get pregnant (she later announced in May 2010 she was 14 weeks pregnant with twins after a sixth treatment of in-vitro fertilization and gave birth to fraternal twins in October).

The unique bilingual arrangement of “O Canada” that was written specifically for Celine’s vocal range was instead used by Nikki Yanofsky.

11. Gretzky in a helicopter basket instead of a pickup truck

One of the most controversial aspects of the Olympic Opening Ceremony was the decision to put Wayne Gretzky in the back of a pickup truck for his journey from BC Place Stadium to Jack Poole Plaza, where he would light the permanent Olympic Cauldron.

In his memoir, Furlong said he did not like the idea from the start, and had proposed to put Wayne in a specially designed basket carried by a helicopter and tracked by spotlights.

“He would have been flying over the city, holding his torch, and then the helicopter would set him down at Jack Poole Plaza,” he wrote. But this was deemed by DAE as unfeasible.

Artistic rendering of Wayne Gretzky on a pickup truck for his journey between BC Place Stadium and Jack Poole Plaza. (Alan Puaca / David Atkins Enterprises / VANOC)

12. Separatist snub on the Opening Ceremony

DAE had spent a considerable amount of the Opening Ceremony budget on a segment that celebrated French Canada, with the segment developed around a well-known, winter-themed Quebec song called “Mon Pays,” written in 1964 by Gilles Vigneault.

The problem: it was a rallying anthem for Quebec separatists, and Vigneault was known to be a fervent separatist.

But in order for VANOC to acquire the rights to use the song, Vigneault mandated that the song “could not be performed anywhere where there was going to be a Maple Leaf displayed” and “could not be used in any kind of setting that effectively promoted Canada as a country that included Quebec.”

These terms and conditions were, of course, unacceptable. And DAE was forced to trash its work.