Written by Brent Toderian for Vancity Buzz

Once a city builds something big, it’s often tough to imagine life without it. Or realize we’d actually be better off without it.

Especially when that big thing has to do with traffic.

Cities around the world have been struggling with this difficulty as they consider the future of their big urban freeways, now well past their best-before dates structurally speaking. Despite this, more and more cities are realizing that spending big money to rebuild something that damaged their city in the first place, lobotomizing their downtowns and waterfronts among many other consequences, might be the ultimate city-making example of throwing good money after bad.

Smart cities are actually tearing down existing freeways, reconnecting their downtowns to their waterfronts, and healing their cities. Boston, San Francisco, Seattle, Seoul Korea, Oslo, Madrid, and well over 100 more cities have shown this boldness. Increasingly it’s not bold at all. It’s just smart.

Vancouver is different. We don’t have to tear down our waterfront freeways, because we never built them in the city in the first place. Our citizens, and eventually our politicians and planners, thought better in the ‘60’s and ‘70’s. They rejected the “free money” from the Feds for the freeways that would have devastated the waterfront, destroyed real neighbourhoods, and blasted through Stanley Park, among other things — heavy costs that would have proved in devastating fashion that there’s no such thing as free money when it comes to doing the wrong thing for your city.

Saying no to freeways was very likely the most important decision earlier generations of Vancouver citizens and leaders ever made. It set our city on the path of counter-intuitive city-building that is today known around the world as ” the Vancouver Model.”

Since then we’ve built a huge amount of housing downtown, more mixed-use and compact communities, and a much more walkable, transit-friendly and increasingly bikeable city. It helped make our city more livable, equitable, green, healthy and economically successful, with better mobility and many more choices for everyone, INCLUDING drivers!

Vancouver has been showing the rest of North America ever since that the only successful way to shorten commute times, reduce car trips, and improve mobility and accessibility, are smarter land-use decisions, and prioritizing walking, biking and transit. The “law of congestion” teaches us that building more roads only adds more traffic and congestion — as the old saying goes, adding highway lanes to deal with traffic congestion is like loosening your belt to cure obesity.

But here’s the thing — there’s an asterisk beside the statement that we dodged the freeway bullet.

That’s because we built a piece of freeway-like infrastructure, two bits of big road thinking actually, that are now left over from our story of freeway rejection. They’re called the Georgia and Dunsmuir Viaducts.

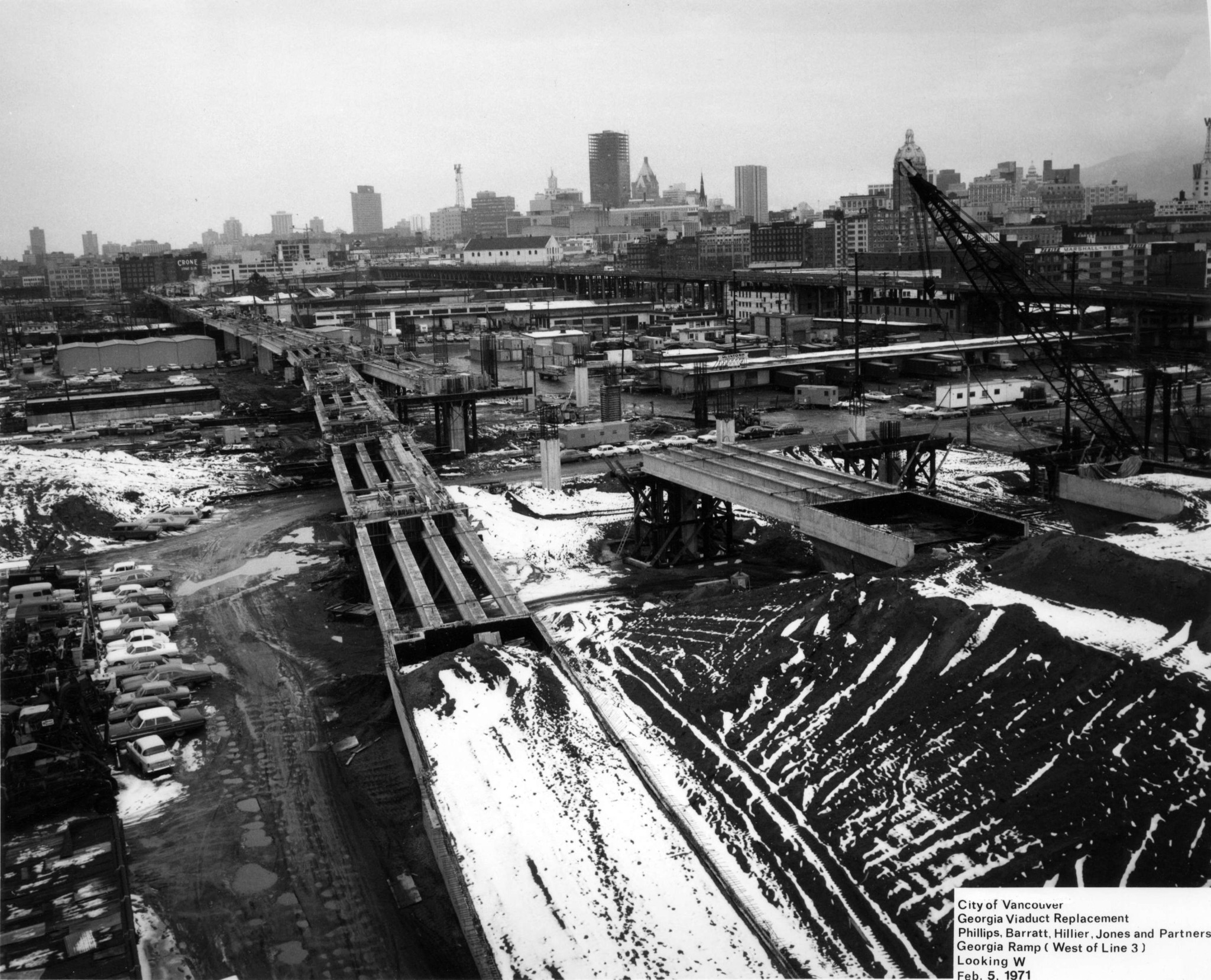

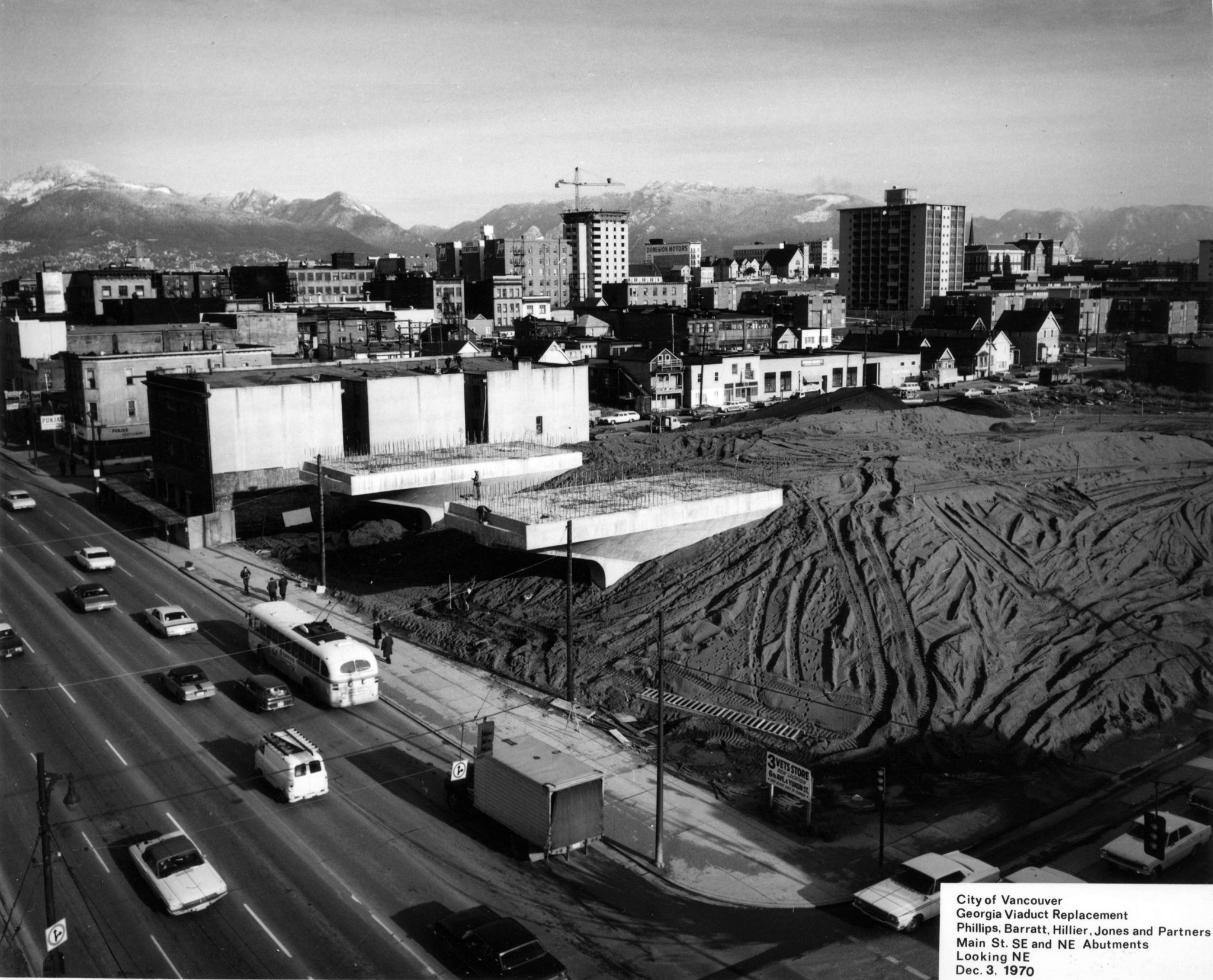

The Viaducts were originally constructed in 1915 to bypass the tidal waters, rail lines and industrial lands below, and were rebuilt in the 1960s as the first piece of that anticipated freeway system that never came.

Image: City of Vancouver

Image: City of Vancouver

Our generation now has a similar opportunity to do the right thing for future generations. We have the opportunity to remove the asterisk and repair the biggest scar in the city, fixing the mistake made before those freeways were rightly rejected. We can tear down those Viaducts and rebuild the city better.

Image: City of Vancouver

Vancouver City Council showed boldness a few years ago, while I was chief planner, by directing staff to begin studying the removal of the viaducts. We had previously stirred the pot by bringing up the future of the Viaducts in our planning work for the North East False Creek area (including the Plaza of Nations), and the False Creek Flats, and had started to make the case internally to “call the question” on their removal. But things really started moving when Councilor Geoff Meggs, who deserves a lot of credit, took the political risk to publically call for an official review. I and my friend and colleague Jerry Dobrovolny, Vancouver’s Director of Transportation, led this work with our fantastic staff team.

Image: City of Vancouver

Our work, and the continued analysis that transportation staff has done since I left city hall, confirmed what most cities now understand — that taking down big car infrastructure doesn’t result in more traffic congestion and gridlock. The system accommodates the change largely through change in human behavior — people rationally rethink their way of getting around, and even where they live.

Not all old traffic engineering models understood this, because they tried to treat transportation like a hard science, like water flowing through a pipe. But people don’t behave like water – they behave like people. Transportation is actually a social science, more like economics than civil engineering. Water doesn’t change its mind. People do.

In short, the world won’t end if the Viaducts go, as we saw when they were closed for the Olympics and for the shooting of the Deadpool movie. The city will work better. The Viaducts are holding us back from a more successful future.

We kick-started the bigger conversation about the possibilities for that better city without the Viaducts through a high profile “ideas competition” in 2011 that attracted remarkable local and international attention. You might remember it, as the resulting designs and ideas covered every front page in the city! The competition, called “re:CONNECT,” attracting 104 submissions from 13 countries – and the public response was fantastic. Over 15,000 votes and over 1500 online comments to the City’s website were generated around the competition, and many powerful ideas (along with some pretty crazy ones) were floated and debated.

Inspired by the winners, and really by the totality of submissions, design work has progressed tremendously since then. The design will continue to get better right up until construction, I suspect. I’ve weighed in lately with comments about the key issues for a successful design, including what NOT to do. I’ll continue to do so. But there’s lots of time to discuss such things – the key now is for Council to make the big decision “in principle” that the Viaduct’s days are numbered.

Image: City of Vancouver

Word from City Hall is that decision may finally come from Council next month. A new staff report is likely imminent, following up on the excellent report that made the case for removal back in 2013. This has been a long process, and a healthy and inspiring conversation. If Council says yes to removal, as they absolutely should, it will quite possibly represent the most important city-making decision this generation of Council will make, building on the wisdom of those previous generations that did right by us.

To make the right decision, we’ll ALL have to see past the city we’ve been, to the city we can be. Ultimately this isn’t about cars or concrete. It’s about making a more connected, sustainable, resilient downtown and city. It’s about the potential for new and better public spaces; social and affordable housing; mixed-use, walkable and transit-supported neighbourhoods; and a better connected city and waterfront, with a healed scar and stronger neighbourhoods where the Viaducts used to be.

A more successful, Viaduct-free future awaits us, Vancouver. We just have to have the vision and boldness to choose it.

Brent Toderian is a city planning and urbanism consultant with TODERIAN UrbanWORKS, advising cities around Canada and the world. He’s Vancouver’s former Director of City Planning, the founding/current President of the Council for Canadian Urbanism, and a regular columnist on “City-Making” on CBC Radio. Follow him on Twitter @BrentToderian.