Written for the Daily Hive by Lani Russwurm at Forbidden Vancouver Walking Tours.

The fate of the little settlement around Gassy Jack’s saloon seemed assured after the Canadian Pacific Railway announced that it would be the terminus for its transcontinental railroad. The new City of Vancouver was incorporated in April, 1886. Two months later it burned to the ground.

The fire was the result of the CPR using brush fires to clear its land for development. June 13 was particularly hot and dry, and a strong wind spread the flames so fast that Vancouver was obliterated in a matter of hours.

Among the few buildings that survived was the Regina Hotel (seen in the above photo) on the southwest corner of Water and Cambie Streets. The only building that still exists from before the fire is the Hastings Mill Store that now operates as a museum at the foot of Alma Street.

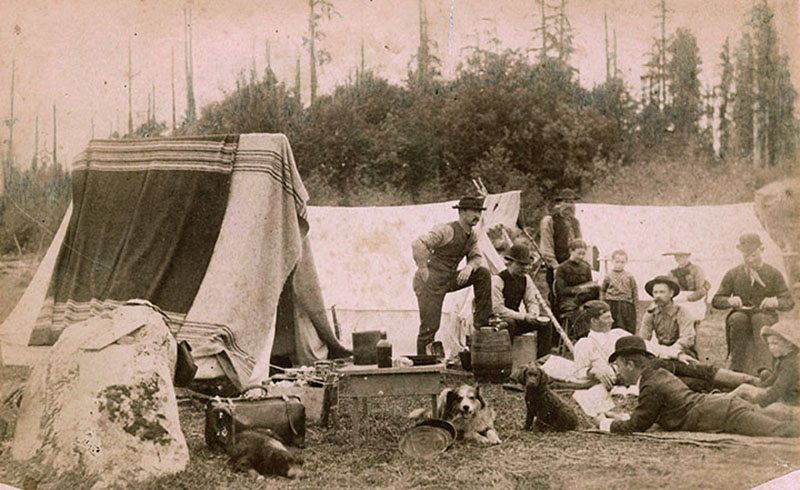

Refugee tent on the southeast corner of Hastings and Carrall Streets after the Great Fire. City of Vancouver Archives #GF P8

Before the smoke cleared, money flooded into town and the job of rebuilding began in earnest. But the true cost was borne not by the buildings, but by the people who lived through it and the ones who didn’t. It was a traumatic baptism by fire, and the ashes of its victims are part of the foundation of Vancouver.

Most people managed to escape the blaze by heading to Burrard Inlet, where they found refuge on the Robert Kerr, a tall ship moored in the harbour. Others rushed to False Creek, where they were rescued by local First Nations people with canoes. Initial reports said as many as 10 people died, but the number of confirmed dead eventually reached more than 20, and the total number is unknown.

Many people escaped the fire by boarding the Robert Kerr, a ship moored in Burrard Inlet. Here it is at the foot of Richards Street in 1886. Photo by JA Brock, City of Vancouver Archives #Wat P48

Many survivors described seeing charred bodies as they frantically fled the blaze. After the fire, George Allen recalled returning to where his hotel had been at the corner of Hastings and Columbia and seeing:

the bodies of six or seven persons, beside the building, in a sitting posture—I could see their watch chains dangling—but quite dead. They looked like persons, sitting motionless, leaning over. I believe they were afterwards identified by their watch chains. Oh, yes, there were six or seven of them; I could not stand that sight; it was too terrible.

Refugee bivouac near the south end of the Westminster bridge, near today’s Main Street and Terminal Avenue, 14 June 1886. City of Vancouver Archives #GF P6

Lewis Carter, on his way back into Vancouver to find out how his hotel fared in the conflagration, reported seeing the body of a woman he knew being carried in a wagon. One side of her body was completely gone, her remaining arm was just a fragment, and she had no hair or eyebrows left.

Sam Macey, C Gardner Johnson, Magistrate John Boultbee came across bartender George Bailey using a wet blanket to swat out flames licking the Balfour Hotel, and joined the effort. Eventually the men gave up, but realized it was too late to flee to safety.

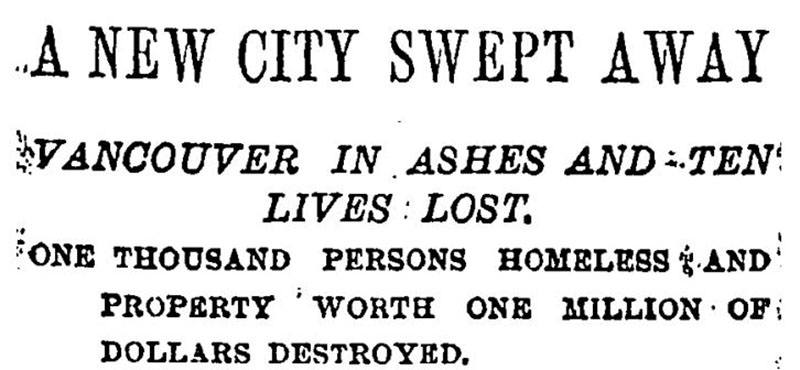

Headline in the New York Times, 15 June 1886.

They spotted a hollow in the street left by a pulled-up tree stump, laid in it, and buried their faces in the gravelly dirt. Bailey’s claustrophobia kicked in. He got up, shouted “I can’t take this anymore! I have to get out!” The other men watched as Bailey burned to his death just feet away, running in circles until he dropped dead.

Then, an abandoned suitcase that was helping protect them from the flames began popping. Bullets inside were exploding from the heat and grazed the back of Boultbee’s head, leaving permanent bald spots and a dramatic story to tell his grandchildren.

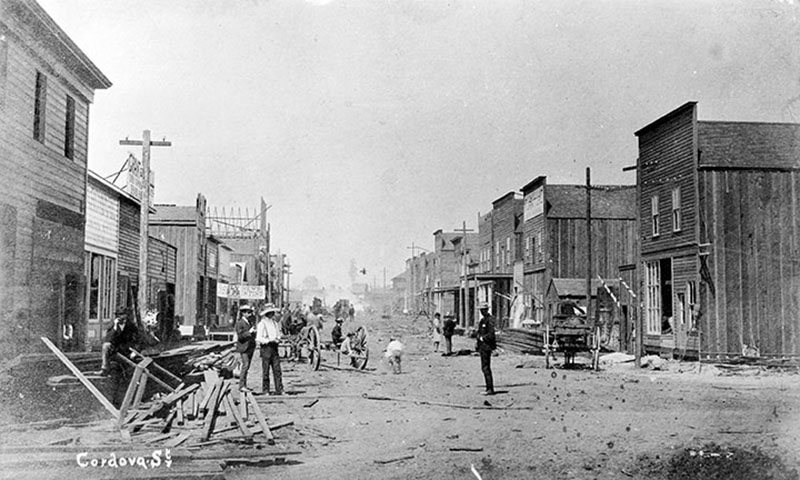

Cordova and Water Streets, four weeks after the fire, Photo by JA Brock, City of Vancouver Archives #Str P129

The intensity of the blaze incinerated many of its victims, leaving only ash and bits of bone. Some people died from suffocation rather than burning. WH Gallagher described one horrific discovery to Vancouver’s archivist, Major Matthews:

Three bodies were taken out of a well … They were evidently husband, wife and little daughter, and must have … saw the fire coming, rushed away, and, seeing a well, jumped into it. There was three or four feet of water in the well, and their clothing was unharmed by fire, but their faces were livid: the fire had, apparently, swirled over the well and they had been suffocated, not burned. They were well dressed; the lady had gloves on her hands. It was the gum and pitch which made the fire so terrible, so fierce, and created a black, bitter smoke more smothering than burning oil.

Cordova Street looking west from Carrall, five weeks after the fire. City of Vancouver Archives #Str P7.1

Remains continued to surface weeks after the blaze during reconstruction.

During renovations in 2007 at the Gospel Mission at 331 Carrall Street, workers discovered a layer of black carbon and ash dating to the 1886 fire. The building was erected in 1889 with an earth-floor basement that sealed the geological record of the fire for posterity.

When walking through Gastown, take a moment to reflect on the fate of those who perished in the Great Vancouver Fire, those whose final resting place is just below your feet. These are the spirits of early Vancouver, and sometimes you can hear their faint, panicky voices echo in the autumn breeze.

For more stories of lost Vancouver souls, check out Forbidden Vancouver walking tour the Lost Souls of Gastown this Halloween season, running every night until November 1.