Story by Andrew Farris, Founder and CEO of the On This Spot app. This is part of a six-part series in which he’ll share some of the photos and history you can find on the app with Daily Hive readers.

See also

- Vancouver Then and Now: Skyline (PHOTOS)

- Vancouver Then and Now: Gastown (PHOTOS)

- Vancouver Then and Now: Chinatown (PHOTOS)

- Vancouver Then and Now: Granville Street (PHOTOS)

Vancouver once had a Japantown. It does not anymore.

In the city’s early days, thousands of Japanese arrived in Vancouver to work in sawmills, canneries and on fishing boats. They set up a vibrant Japanese neighbourhood centred around today’s Oppenheimer Park. It became known as “Little Tokyo” and was the biggest concentration of ethnic Japanese, or Nikkei as they became known, in Canada.

Like the Chinese, the Nikkei were subject to all kinds of racism intended to make their lives difficult. Nevertheless, they worked hard to integrate into Canadian society and made many attempts to prove their loyalty to Canada.

Some 200 Nikkei tried to enlist to fight with the Canadian army in World War I but they were rejected by the B.C. government. The government feared that if they were allowed to fight and die for Canada, they would soon demand the right to vote. Those 200 men travelled to a recruiting station in Alberta where they were accepted. They fought bravely in the trenches with the Canadian Expeditionary Force and 54 were killed.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the Nikkei still struggled to gain acceptance in society. The one place they were able to compete on an equal footing with white Canadians was on the baseball field. The Vancouver Asahi, an all-Nikkei team based at Oppenheimer Park, became the best in the province. They won the league championship five years in a row and were celebrated all around British Columbia.

Then Japan attacked Pearl Harbour. Canada and Japan went to war and everything changed.

In 1941 and 1942, white British Columbians had an almost hysterical fear of Japanese invasion. The public demanded the removal of all the Nikkei from the coast so they could not act as spies or saboteurs for the Japanese. The federal government agreed and in February 1942 all the Nikkei, even those born in Canada, who had never been to Japan, were rounded up and sent to awful internment camps in the Rocky Mountains. All their property was auctioned off at bargain basement prices and after the war none of it was returned. Almost overnight the thriving neighbourhood of Japantown ceased to exist. It was one of the most disgraceful episodes in Canadian history.

After the war, the Nikkei were discouraged from ever returning to Vancouver. Given their horrible treatment, it is not surprising few did. Overtime, the neighbourhood where Japantown once stood, in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, became skid row, an area infamous for its poverty and drug abuse.

The Secord Hotel in 1890

1890: The Secord Hotel on Powell and Dunlevy offered cheap room and board and was but one of dozens of boarding houses serving workers at the Hastings sawmill. At this point many of the Japanese immigrants had yet to arrive, and it would not be for another decade till Japantown would begin to take shape here.

1890: The Secord Hotel on Powell and Dunlevy offered cheap room and board. (Vancouver Archives)

On this spot now…

(On This Spot)

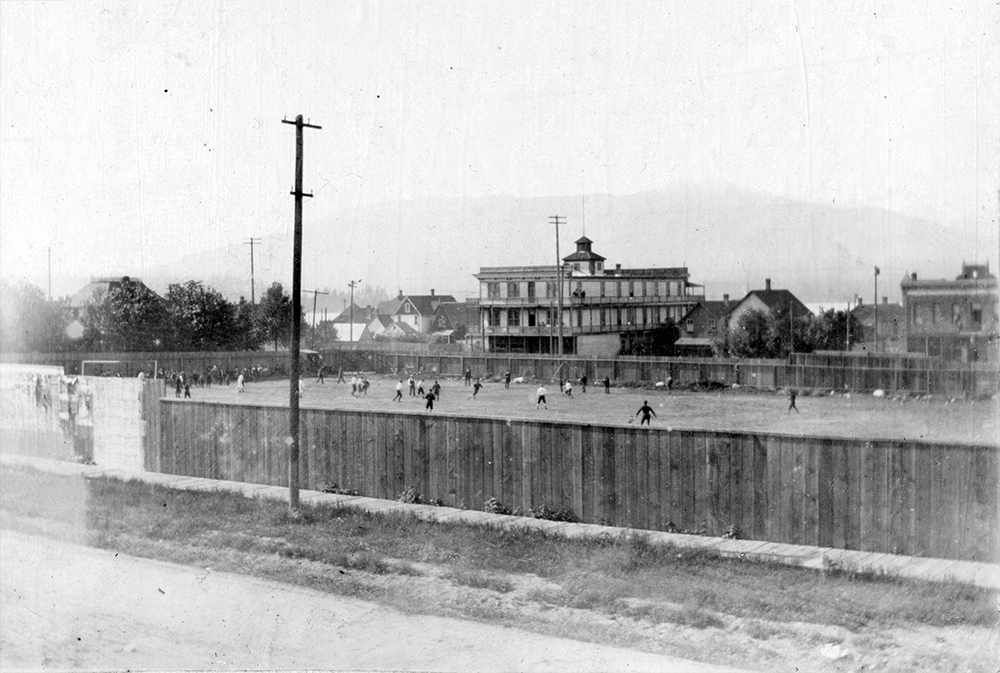

Powell Street Grounds in 1897

1897: A baseball game on the Powell Street Grounds, today’s Oppenheimer Park. Many Nikkei took to baseball like fish to water, and the legendary baseball team, the Asahi made this its home field. For a time the Asahis were the most popular baseball team in the province, and they were the subject of a major Japanese movie in 2014. The movie is a fascinating Japanese take on 1930s Vancouver.

1897: A baseball game on the Powell Street Grounds, today’s Oppenheimer Park. (Vancouver Archives)

On this spot now…

(On This Spot)

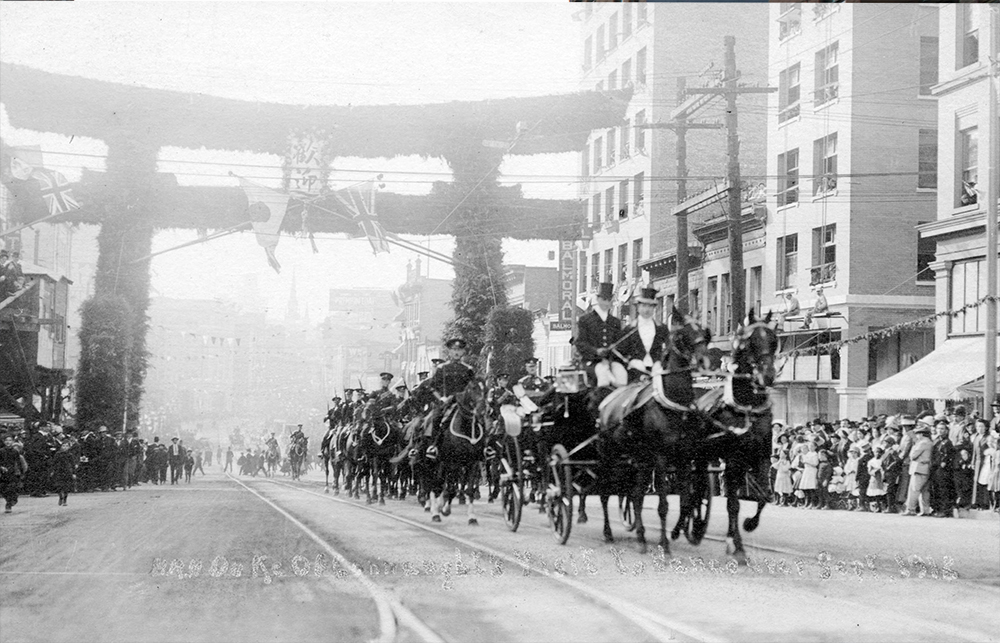

Main and Hastings in 1912

1912: The Duke and Duchess of Connaught pass under a welcoming arch erected by Vancouver’s Japanese community on Hastings and Main. The crossed flags are a sign of the close ties between the British Empire (including Canada) and the Empire of Japan, who signed an alliance in 1902.

1912: The Duke and Duchess of Connaught pass under a welcoming arch erected by Vancouver’s Japanese community on Hastings and Main. (Vancouver Archives)

On this spot now…

(On This Spot)

Japanese Hall in 1927

1927: This was the Japanese Hall and Language School on Alexander Street, the centre of the community life in Japantown. It was the only piece of property ever returned to the Nikkei after the war. During the war the Nikkei were dispersed across the rest of the country and discouraged from ever returning to British Columbia, which they were only legally allowed to do in 1949, four years after World War II ended.

1927: This was the Japanese Hall and Language School on Alexander Street, the centre of the community life in Japantown. (Vancouver Archives)

On this spot now…

(On This Spot)

Tairiku Headquarters in 1927

1927: This was the headquarters of the Tairiku on Cordova Street, the second of eventually four Japanese newspapers in Japantown. When the Nikkei were interned in 1942, 70 men hid out here from police before surrendering and being exiled to the interior.

1927: This was the headquarters of the Tairiku on Cordova Street, the second of eventually four Japanese newspapers in Japantown. (Vancouver Archives)

On this spot now…

(On This Spot)

Funeral procession in 1929

1929: The crowds here have gathered for the funeral procession of a prominent member of the Nikkei community. They are standing in front of the Powell Street United Church, which has since been replaced by the Buddhist Church. At the time this church was a major hub for the Nikkei community. The homes at the right are still standing.

1929: The crowds here have gathered for the funeral procession of a prominent member of the Nikkei community. (Vancouver Archives)

On this spot now…

(On This Spot)

Fuji Chop Suey Restaurant in 1931

1931: The Fuji Chop Suey restaurant, one of Vancouver’s most popular restaurants in the 1930s. A Japanese take on Chinese cuisine, this was but one of the over 500 Japanese businesses that sprouted up in Japantown. Japanese businesses took decades to come back to Vancouver after the internment. Hard as it is to believe today, from the 1950s to the 1980s there were only two or three Japanese restaurants in all Vancouver.

1931: The Fuji Chop Suey restaurant, one of Vancouver’s most popular restaurants in the 1930s. (Vancouver Archives)

On this spot now…

(On This Spot)

Traditional parade in 1937

1937: Crowds watch Japanese women and girls in traditional clothes taking part in a parade down Powell Street. While the first wave of immigrants from Japan were predominantly men, soon many women joined them and had children, creating a well-balanced community.

1937: Crowds watch Japanese women and girls in traditional clothes taking part in a parade down Powell Street. (Vancouver Archives)

On this spot now…

(On This Spot)

Powell Street in 1939

1939: Two Nikkei cross Powell Street by a lightpost emblazoned with the Union Jack. All the way up to 1942 the Nikkei made strenuous efforts to show their loyalty to the Canada and the Empire. It did them little good. Sergeant Masumi Mitsui was one of the 200 Nikkei who fought for Canada in World War I, and he had won the Military Medal for his heroism at the gruesome Battle of Hill 70. After Japan and Canada went to war in 1941, he wrote to the Minister of National Defence on behalf of all the Japanese-Canadian veterans, pledging “their unflinching loyalty to Canada as they did in the last war.”

1939: Two Nikkei cross Powell Street by a lightpost emblazoned with the Union Jack. (Vancouver Archives)

On this spot now…

(On This Spot)

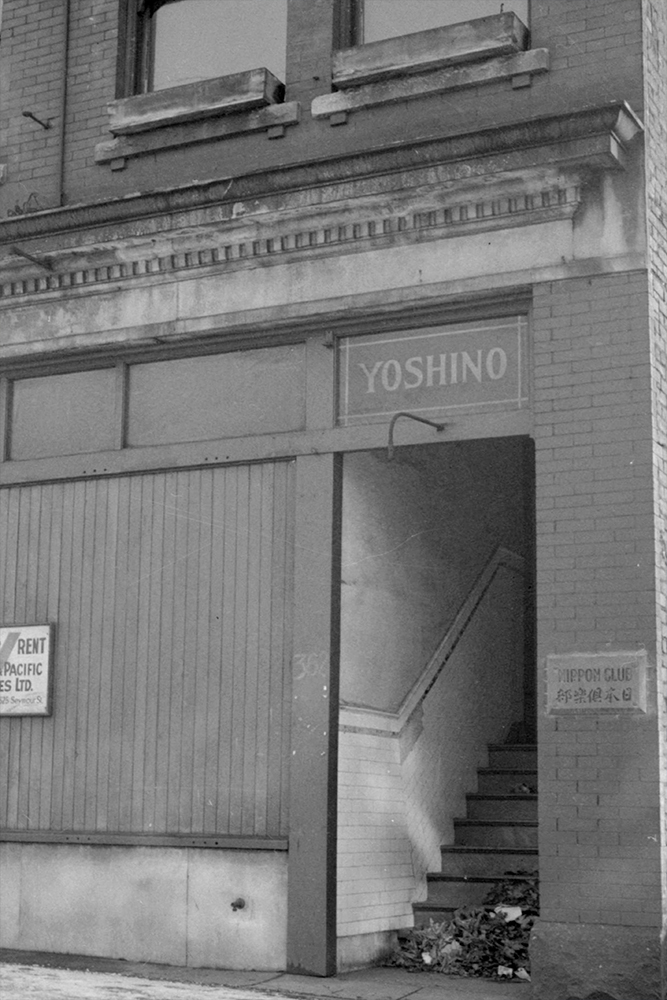

Nippon Club in 1942

1942: The abandoned Nippon Club, a social gathering place for Japanese-Canadians on Alexander Street, shuttered in the spring of 1942. When the order to intern all the Nikkei came in, Sergeant Mitsui went to the registration office for Japanese Canadians and flung his medals on the official’s desk. “I served my country. You’ve taken everything from me. What are the good of my medals?” He was not exempt, and sent to an internment camp in the mountains.

1942: The abandoned Nippon Club, a social gathering place for Japanese-Canadians on Alexander Street. (Vancouver Archives)

On this spot now…

(On This Spot)

What Do I Remember of the Evacuation?

Joy Kogawa was a little girl when she was sent to the mountain camps in 1942 for internment as an “enemy alien”. Years later she wrote this heartbreaking poem, What Do I Remember of the Evacuation?

I remember my father telling Tim and me

About the mountains and the train

And the excitement of going on a trip.

What do I remember of the evacuation?

I remember my mother wrapping

A blanket around me and my

Pretending to fall asleep so she would be happy

Although I was so excited I couldn’t sleep

(I hear there were people herded

Into the Hastings Park like cattle.

Families were made to move in two hours

Abandoning everything, leaving pets

And possessions at gun point.

I hear families were broken up

Men were forced to work. I heard

It whispered late at night

That there was suffering) and

I missed my dolls.

What do I remember of the evacuation?

I remember Miss Foster and Miss Tucker

Who still live in Vancouver

And who did what they could

And loved the children and who gave me

A puzzle to play with on the train.

And I remember the mountains and I was

Six years old and I swear I saw a giant

Gulliver of Gulliver’s Travels scanning the horizon

And when I told my mother she believed it too

And I remember how careful my parents were

Not to bruise us with bitterness

And I remember the puzzle of Lorraine Life

Who said “Don’t insult me” when I

Proudly wrote my name in Japanese

And Tim flew the Union Jack

When the war was over but Lorraine

And her friends spat on us anyway

and I prayed to the God who loves

All the children in his sight

That I might be white.

– Joy Kogawa

The On This Spot app offers you a guided tour of Vancouver’s historic photo spots and allows you to create your own then and now photo mash-ups as you walk around.

The app launched in Vancouver this year, but will expand to other major cities in Canada and the US soon – if you have a talent for writing history tours, On This Spot wants to know.

To download the app for Android or iPhone, for more info or to contact Andrew, check here: onthisspot.ca